“Try to love the questions themselves, like locked rooms and like books that are written in a very foreign tongue. Do not now seek the answers… Live the questions now.”

— Rainer Maria Rilke, Letters to a Young Poet, trans. M.D. Herter Norton (New York: W. W. Norton, 1934), p. 35

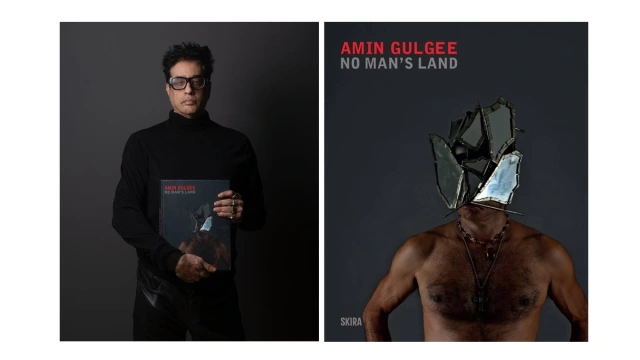

We met in Paris. It was a very hot summer day. The imposing golden dome of Les Invalides, with the quiet solemnity of Cathédrale Saint-Louis as backdrop and the murmurs of the Paris-Chartres pilgrimage trailing into hymns, our conversation took shape. Amin Gulgee had brought his new monograph, No Man’s Land, and amidst the ritual chorus of pilgrims and the smog of war – India and Pakistan, always teetering – he said it: “They should bomb me first.”

It wasn’t bluster. It was a declaration, an invocation. We were no longer just discussing a book; we were discussing a book. We were stepping into its psychic terrain – into that volatile expanse Gulgee calls No Man’s Land, where the body becomes site, the nation unravels, and the sacred is neither whole nor broken, but always in flux.

The phrase conjures wartime desolation – the ground between trenches, soaked in threat. But Gulgee reimagines it. In his monograph, and indeed in his very practice, No Man’s Land becomes a threshold: between gender and genderlessness, presence and withdrawal, devotion and undoing. His work is not simply interdisciplinary; it is alchemical. It moves through sculpture, performance, curation, and architecture, not to occupy them, but to fracture them. Meaning here is never stable. It flickers, resists. It refuses finality, inviting us to see the world in a new light.

The 414-page monograph, published by Skira and designed by Kiran Ahmad, and edited by the deft John McCarry, is a testament to this. It resists codification, offering a hauntological rather than retrospective view. It is not archival, but shamanic. Twelve contributors gather not in consensus but in revelry, like attendees of a sacred, chaotic salon. ‘A party where everyone can do what they want,’Amin quips. But it’s more than that: it’s a curatorial séance, a ritualised act of shared unknowing.

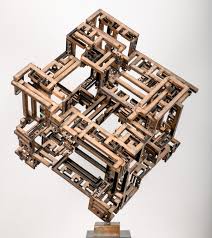

From the first page, No Man’s Land resists linear reading. It is, as Gulgee himself, polyphonic. His sculptures, often forged in copper and bronze, are not inert. They breathe, corrode, and transmute. They are saturated with Qur’anic fragments, geometric scars, and the intimacy of spiritual decay. Here, metal does not denote permanence. It bears witness to loss.

Islamic art historian Oleg Grabar lends a crucial interpretive frame, connecting Gulgee’s calligraphic geometries to the sacred architecture of Islamic abstraction. These are not ornaments but ontologies—Square Kufic as spiritual cypher. The repetition of geometric motifs is not merely decorative; it is meditative and ecstatic—a discipline of presence. But Kishwar Rizvi sees deeper into the patina. The erosion, she argues, is an epistemological phenomenon. The decay is not a defect but a doctrine. The sculptures are not representations. They are altars to time, devotional architectures of corrosion and sediment.

Ethos of refusal

And nowhere is that ethos of refusal more vivid than in his curatorial method – what one might call a choreography of chaos. Walking through an Amin Gulgee exhibition, especially at his Karachi gallery, is not like tracing a curatorial argument. It is like stepping into a storm – or a dream. There are no wall texts to guide you, no didactic labels imposing coherence. Instead, there is simultaneity. Objects and bodies speak at once. Artworks bleed into performances. Sculpture mingles with scent, with sound, with chant. The viewer is not shown a way. They must find their own, becoming an integral part of the artistic experience.

His model is closer to a Sufi whirling than to a biennial blueprint. His curation blurs authorship, collapses hierarchies, and rejects the sterile clarity of taxonomy. Artists are invited not to exhibit but to inhabit. Rooms become rituals. Installations become processions. It is not that order is absent—it is that order is multiple, fugitive, layered. His exhibitions unfold in spirals, not lines. And this spiralling is not aesthetic affectation. It is a philosophical commitment. Gulgee offers a radical ethics of confusion. One that welcomes contradiction, cultivates friction, and privileges encounter over resolution, challenging traditional art practices and inviting us to rethink our understanding of art.

In a world obsessed with mastery and branding, his curatorial vision insists on generosity—on trusting the audience to dwell in ambiguity. He curates not to explain but to open space. The gallery becomes not a white cube, but a home. A portal. A sanctuary for the difficult, the half-formed, the luminous. In many ways, his curatorial method is the antithesis of institutional practice. It resists the polished machinery of art markets and museum retrospectives. Instead, it feels like a collective breath. A communion. A challenge.

Bloodline

We must not forget the bloodline. Amin is the son of Ismail Gulgee, whose portraiture and calligraphic compositions remain enshrined in the Pakistani modernist canon. But Amin is no heir. “My father’s work has nothing to do with mine,” he says, not as rejection but as rupture. This is disinheritance as ritual. He doesn’t refute the father. He performs the exit. If his father was a heroic chronicler of form, Amin is its exorcist. He does not sculpt lineage. He interrupts it. That gesture of refusal, however, is not rage—it is ritual. In stepping away from the patriarchal canon, he does not merely critique it; he also challenges it. He mourns its hold, buries it in the very metals he forges.

And yet, in a gesture as tender as it is complex, he has built the Gulgee Museum—a sanctuary for his father’s work, and for the legacy he once claimed no part of. This is not a contradiction; it is devotion without submission. To disinherit is not always to discard; it can also mean to exclude. Sometimes, it is to make space anew. The museum is no mausoleum. It is an act of resurrection, a sculptural embrace across generations. In its curation is a quiet love—one artist recognising another, not through lineage, but through light. Where the father’s brush once defined glory, the son’s architecture now shapes remembrance. It is the most radical kind of homage: one born not of imitation, but of reverent divergence.

His Karachi home is no domicile. It is part reliquary, part stage, part trap. Sculptures erupt from the floors. Mirrors fragment perception. It is not a space one visits. It is a space in which one is initiated. And the gallery—not quite a museum, not quite a studio—operates as a liminal vessel. It is itself No Man’s Land. Within its mirrored corridors, performance bleeds into curation, and sculpture becomes site-specific theology. The visitor doesn’t merely observe. They are ensnared, transformed.

Editorial Scaffold

Maryam Ekhtiar’s conversation with Amin offers a rare moment of stillness. In it, he speaks of process not as a concept but as compulsion. There are no sketches, no plans—only hours of movement, breath, and refusal. The studio becomes liturgy. The sculpture, mourning. This is not a craft. It is an invocation. The hands do not follow the mind. They follow memory—bodily, ancestral, intuitive.

He describes sculpting as an act of possession. The metal resists him. The fire confronts him. There is no mastery, only participation. Sculpture emerges from encounter, from the wound of the moment. This understanding repositions the artist not as creator, but as vessel. The studio is not a workshop but a shrine. Each piece was an answered prayer.

The 2010 performance, Healing, is an anchor. After the violent deaths of his parents, Gulgee allowed his head to be shaved by fellow artists. Hair, that most corporeal remnant, falls like ash. It is grief enacted, offered, and released. The ritual was repeated during the pandemic, this time in solitude. Through body, through bronze, memory is not preserved. It is transmuted. The head becomes the altar. Loss becomes form. What is remarkable here is not the performance’s aesthetic but its vulnerability. It is not staged, but suffered. Not enacted, but endured.

Performance, in Gulgee’s hands, is sculpture without permanence. H.M. Naqvi captures its viscosity. His prose pulses, tracing Amin’s shirtless gestures, his mirrored corridors, his volatile presence. Sculpture, here, is not fabricated. It is inhabited. Gulgee’s body is not just medium. It is an invocation. And invocation requires offering. To watch him perform is to witness a form of spiritual immolation—a burning of boundaries between artist and artwork.

Alexi Worth extends this: the artist himself is a sculptural form. His clothing, voice, and posture—all tools of spatial intervention. Not costume, but charisma as a medium. Worth understands that Gulgee’s body, like his work, flickers between icon and echo. In his flamboyance lies form. In his silence, a liturgy. To perform is not to act, but to transgress the static.

Even Amin’s public persona is performative architecture. His gestures in interviews, his stage presence, his refusal to reduce his practice to digestible bites—all of this becomes part of the work. His life is not a biography. It is a performance score.

Gemma Sharpe places him among performance artists like Marina Abramović, Durriya Kazi, and the late Ali Imam, but notes that his rituals are never global abstractions. They are rooted in Karachi’s psychic topography—in botal gali (perfume bottle street), in char-bagh, in the sacred vernacular. His performance is a site-specific invocation, where the city itself becomes a participant. Gulgee stages Karachi not as a backdrop, but as a collaborator. It’s decay, its riotous beauty, its noise, all folded into the work’s very breath.

The inclusion of QR codes in the monograph is no gimmick. It is an extension. Sculpture becomes video. Performance becomes an archive. The book does not describe the work. It performs it. It flickers like a mirrored corridor: gesture, pause, disappearance. The reader does not simply read. They traverse. It is a portal, not a record. And as we enter, we become implicated—unmoored, remade.

It is both startling and scandalous that this is Amin Gulgee’s first major monograph—thirty years of radical presence, and still the silence of institutions. Akbar Naqvi’s glib dismissal in Image and Identity cast a long, shameful shadow. But this volume refuses to correct history. It chooses instead to outsing it. To create where critique has failed. To gather where the gatekeepers are dispersed.

Quiet Revolution

No Man’s Land is not tidy. It does not seek completion. It thrives in tension: between geometry and flesh, between decay and invocation. It is both deeply Islamic and radically queer. It is both post-national and insistently local. Its achievement is not that it explains Amin Gulgee. It cohabits with him. It is kin, not chronicle.

One does not finish this book. One exits it, as from a dream half-remembered. The gestures linger: the rust of copper, the chant of a verse, the glint of a broken mirror. Meaning, always, just out of reach. And in that distance, something holy.

This is Amin’s ethic. To dwell in the in-between. To sculpt from silence. To perform in the absence. In an age of manic certitudes—of nation, of masculinity, of legacy—he invites us to the threshold. And waits there. His invitation is not to resolution, but to residence—to inhabit the question rather than rush the answer.

We did not conclude our dialogue in Paris. We wandered it. A maze of glinting walls, echoing hymns, and no fixed exits. And in that wandering, we entered his practice. Not as spectators, but as echoes. Not as readers, but as pilgrims.

Amin Gulgee does not sculpt monuments. He sculpts mirrors. And when we look in, we do not find a reflection. We find a rupture. We find ritual. We see the trace of something unnamed—and unnamable.

Here, in No Man’s Land, the only certainty is the courage to stay uncertain.

And that, in the end, is the work’s quiet revolution.

It is an ethic of becoming. An aesthetic of surrender. A theology of the in-between.

It is a home for those who have none. A sanctuary for the fragmented. A shrine to that which flickers, refuses, persists.

To read this book is to enter a corridor without a map or compass. It is to relinquish certainty.

And in that relinquishment, to find not knowledge, but witness.

To close this book is not to conclude it.

It is to begin.

It is to walk, slowly, into No Man’s Land—barefoot, breath held, eyes open.

Narendra Pachkhede will be in a conversation with Amin Gulgee at International Art Gallery Forum at the Dubai World Trade Centre on July 21, 2025.