Sultan Somjee, an African humanist’s quiet revolution in how we walk, remember, and reconcile, grounded in a relational humanism rooted in the philosophy of Utu.

The step, trivial and unremarked, is a small act of covenant.

To walk is to re-enter that covenant again and again, each stride a renewal of belonging. The step is the thought before it has found its words. Modernity, of course, conspired to forget this. Asphalt and acceleration turned the walker into a nuisance. The flâneur of nineteenth-century Paris, Baudelaire’s “botanist of the sidewalk”, was already a figure of resistance, drifting through the commodity arcade, seeing rather than buying. Today the flâneur is endangered. Surveillance, privatization, and the tyranny of the algorithmic map have narrowed the possibility of aimlessness. To walk without destination has become a minor act of civil disobedience.

This intimacy between movement and meaning is older than language. Long before narrative, there was the path. The first stories were itineraries of hunting and gathering: where the water lies, where danger begins, where ancestors sleep. Every road remains a palimpsest of intentions, devotional, mercantile, desperate. To walk a road is to enter a text written by countless others. One never walks alone. Each stride interprets the world anew, translating topography into experience. Knowledge, here, is not extracted but absorbed.

Anthropology once understood this. Fieldwork was footwork. The ethnographer’s first instrument was the sole of the foot. But scholarship forgot its body. Sultan Somjee, the Kenyan ethnographer and thinker of indigenous knowledge and reconciliation traditions, reminds us of the older truth. Among pastoral communities, he says, reconciliation begins as choreography before it becomes speech. Enemies must first share a rhythm, carry water together, walk the same dust, listen to memories of the land they share, they revere it and they have walked it. “The walk restitches being,” Somjee tells me. The world is not remade at the negotiating table. It is repaired, step by step, where the ground remembers what the tongue cannot say.

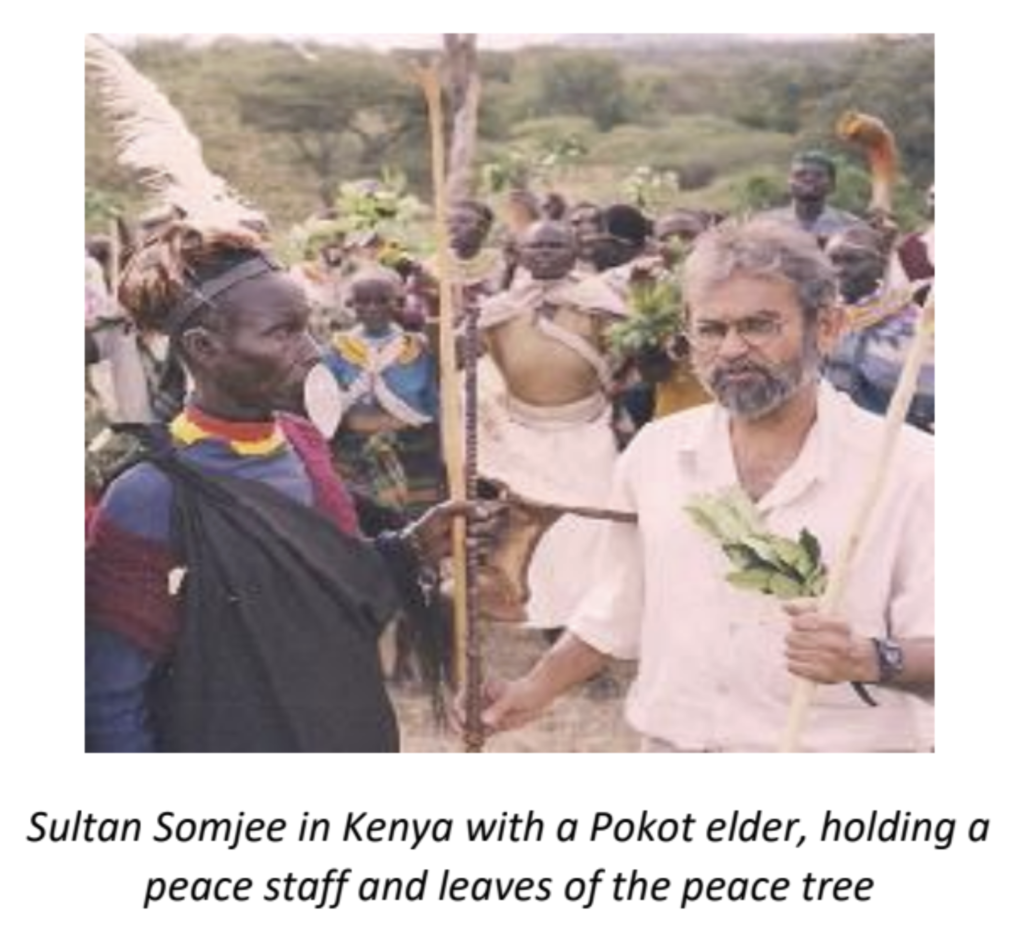

In Sultan Somjee’s world, Utu is not an idea to contemplate but a path to walk. Each footfall maps Utu onto terrain and memory. Peace is not theorised; it is carried like the peace staff passed between elders. The staff authorises speech not by decree but by touch. Objects remember the warmth of the hands that held them, the rhythm of words once spoken through them. Such gestures reveal what philosophers call the moral imagination, the capacity to feel the weight of another’s life as if it were one’s own.

And yet, every serious walker knows the other half of this knowledge: solitude. Aloneness is not the absence of others but the presence of the world. The wind and the noise of leaves become extensions of thought. One can be most communal when most solitary, most attuned to humanity when most withdrawn from it.

There are lives that embody that paradox, moving quietly, as if in step with the earth. Sultan Somjee’s is one of them.

“I never prepared for my walks,” he told me. “Not inwardly, not outwardly. I began each journey knowing only the destination. I carried no compass, no map, no plan for what I wished to see or learn. My body led the way, and my senses were the only instruments of direction. Whatever unlearning happened did so through openness. I had to relinquish the desire to plot an outcome, to accept the unknown without fear, to trust that the land would instruct me if I simply placed one foot before the other.”

An ethnographer, writer, poet and artist, he has walked much of Kenya not in pursuit of discovery but of listening. While the post-colonial state measured progress in roads and imported expertise, Somjee turned to the unrecorded traditions that endured beneath those metrics: the reconciliation rituals of pastoralists, the gestures of elders who spoke through silence, the ceremonies by which communities restored balance with the land after blood had been spilled.

From his years as Head of Ethnography at the National Museums of Kenya to his founding of the Community Peace Museums Heritage Foundation, Somjee built what might be called an infrastructure of conscience: small, rural museums across Kenya, Uganda, and South Sudan devoted to preserving the moral imagination of peace. Between 1994 and 2003, he developed this network as a living archive of Indigenous reconciliation practices.

In 2001, the United Nations named him one of twelve Unsung Heroes of Dialogue among Civilizations, citing “his pioneering work in preserving indigenous peace traditions and developing community museums that foster reconciliation through culture and heritage” (United Nations Department of Public Information, DPI/2215, “UN Names 12 ‘Unsung Heroes’ of Dialogue Among Civilizations,” 4 September 2001).

Yet his truest archive may be his body in motion. One Who Dreams Is Called a Prophet (2020), a six-hundred-page fictionalised memoir launched in 2020 by his longtime friend and collaborator Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, is not only a book about peace, it is a book that walks. Its protagonist, Alama, Somjee’s alter ego, traverses the arid expanse of East Africa in search of Utu, an African philosophy of being human. “Prophets,” Ngũgĩ said at the launch, “are very conscious and connected to the land and environment.” For Somjee, that consciousness is not metaphorical. It is the pulse of footsteps in dust, the cadence of breath aligned with horizon.

Utu, from the Swahili mtu, meaning “a person”, names an armature of relation in which humanity is inseparable from community, ancestors, and nature. To say “I am because you are” is not a moral aphorism but a sensory truth. In South Africa it finds cognates in Ubuntu; in Gĩkũyũ, Ngũgĩ calls it Ūmūndū. All describe a relational ontology where peace is not an agreement but a vibration felt in the body, like the heartbeat of the land itself.

When I first heard Somjee, he spoke not of institutions but of journeys. He recalled travelling as a child between Nairobi and Arusha, watching through a car window as Maasai pastoralists crossed the plains. “I saw them as me,” he said. That gaze, half envy and half revelation, seeded the inquiry that would define his life: how walking becomes a form of knowing.

I caught up with Sultan to gather his thoughts on walking, on how movement shapes the making of peace and the founding of peace museums. What followed was less an interview than an unfolding, a movement between memory and philosophy, between the body and the land that receives it.

In One Who Dreams Is Called a Prophet, Alama’s walk begins in Turkanaland and moves through Garissa, Kibera, and Wamba, landscapes scarred by colonial partition and modern elections. His encounters mirror Somjee’s own fieldwork: conversations with elders, peace rituals beneath acacia trees, and confrontations with the bureaucratic theatre of Western “liberal peace”. The journey ends not with arrival but with a question: can peace exist when one is severed from land, or when land itself has grown “hot with anger” from the blood it has absorbed?

To walk, in Somjee’s philosophy, is to trace the moral cartography of a place, to move through history without the armour of abstraction. His life’s work, from introducing Indigenous aesthetics into Kenya’s school curriculum to creating museums where reconciliation is enacted rather than displayed, is a long act of walking back toward humanity.

Somjee reminds us that peace is not a condition but a practice of being human. In a century defined by displacement and noise, his insistence on listening to the land feels prophetic in the truest sense, not foretelling the future but recalling a wisdom we have forgotten. We began with the first path as he spoke of how Utu had once animated the continent, a lived moral fabric that guided relationships between people, ancestors, and the land.

Listening to the land

I asked him what first drew him to walking as a form of inquiry, not travel.

He smiled, as if the question had been waiting for years. “I used to travel a lot between Nairobi and Arusha from the late 1940s,” he began. “That whole journey is Maasai territory. I would watch the pastoralists through the car window and wish I were there with them. The scene spoke of freedom, openness, of nature alive with animals grazing and standing still around the walkers. I saw them as me.”

He paused, the memory passing through him like wind. “Later, as an adult and a researcher, I watched again, this time from a bus window crossing the arid lands of northern Kenya. My gaze went far into the land and into the bodies of the walkers. My inquiry was through that gaze, into the feelings in my body. My senses travelled to where they walked.”

“The land did speak,” he said. “It spoke in serenity and in turbulence, in the pulse of wind that felt like a heartbeat, in the shifting colour of the sky that mirrored the water below. Sometimes it was quiet and inviting. Other times storms rose without warning, rivers swelled in anger, and danger hid beneath the calm surface. To walk there was to walk inside a living being whose moods one could never fully predict. Those images stayed with me. They taught me to listen with more than my ears.”

For Somjee, this looking was never detached. It was not the anthropologist’s gaze but something closer to reverence. “That is what I write about in Bead Bai and Home Between Crossings,” he said. “The body remembers what the eye feels.”

He laughed softly when he spoke of his youth. “As a scout I walked, we went on long walks, we called it hiking. It sounded more military, a test of toughness. We thought we were heroes.”

He grew thoughtful again. “If my walking in those years was inquiry, it was unconscious. My feelings were registering and being archived until I wrote One Who Dreams Is Called a Prophet. Dr. Kimberly Baker, who is writing my life narrative, calls Alama my alter ego. I think she is right. Alama walks where I once only looked.” In 2021, Dr. Baker defended her PhD thesis, Wayfinding Peace: Museums in Conflict Zones, on Sultan Somjee’s life’s work at the University of British Columbia.

Away from Nairobi, the sensation became a quiet liberation. “Leaving the city I often whispered to myself that freedom had finally arrived,” he said. “My hands carried almost nothing. My heart carried joy. Beauty and freedom waited on the path ahead.”

That hung in the air with a quiet intimacy, as though Alama himself had entered the room, a shadow twin, walking alongside.

I asked him, “How does the land itself teach peace — through silence, through hardship, through endurance?”

“Land,” he said at last, “is a cognate of Utu. I became aware of land as Utu through the pastoralist’s body. I went into my feelings rather than into the mind. I never made academic inquiries.”

He spoke slowly, as if each phrase were shaped by the rhythm of footsteps. “Land is called to be a witness in traditional reconciliation rituals. Dances thud their sounds and rhythms into it, and the land responds. I watched this, absorbed it at Kamĩrĩthũ, and in African dances off stage, unchoreographed, alive. When people and animals walk — cattle, goats, camels, even the wild ones, they speak to the land in rhythm, and the land speaks back through their bodies. I write about this in One Who Dreams Is Called a Prophet.”

To Somjee, the land was not inert soil but a living elder. “It is there as a living presence, like a grandfather who bears dignity in silence,” he said. “You hear his breathing, and if you are close enough, his heartbeat. The land holds hardship, the whole embodied history of remembrance. Yet it does not teach peace. It simply is. It says: I am because you are.”

“Alienation from land makes a refugee-beggar through displacement,” he said, as though remembering something painful. He had seen it happen, pastoralists who once walked proudly across the plains, adorned in beads and colour, reduced to strangers in towns. “I cried when I saw them,” he said. “They were dreaming of return — to their land, their ancestors, their peace.”

He looked down at his hands. “The scenes I write through Alama’s eyes are what I saw and felt myself,” he said. “They were seeking peace through silence, through hardship, through endurance, dreaming to work the land again and sleep on it at night. I felt it in them, because I had sensed land in them while living among them.”

Then he smiled softly. “Since then, I like to sleep directly on the earth, as if in my mother’s lap. As Alama does.”

He paused once more, then added a small, radiant detail. “When my first son was born forty-three years ago, I named him Ardhiat – of the land,” he said. “In Swahili, ardhi means land. Ardhiat Somjee lives in Australia now. But the name, it walks with him.”

I asked him, “Do you remember the first elder who taught you something through a walk, not through words?”

He smiled, shaking his head. “There was no one elder,” he said. “Usually I walked with two or three, sometimes only one. The walks were mostly silent, but we were aware of each other — our breath, our steps. Gradually, I learned to be aware of the land itself.”

“People imagine I walked as leisure walkers do,” he added. “In truth I walked because I had no landrover and because fieldwork demanded it. I moved from village to village sketching the material culture I observed. I walked alone most of the time. Now and then an elder would appear on the path. If I greeted him with the respect of my age group in the etiquette of Utu, he might walk beside me for a while, never asking why I walked on his land, never expecting me to explain. Words were not necessary. Our steps did the speaking.”

He described those journeys not as lessons but as presences. “I could sense them wondering about me,” he said. “I was the odd one, a stranger. Not a nearby tribal fellow, not a white tourist either. They saw me as an Indian from the duka in town — the man who sold sugar, salt, a box of matches, some tea leaves. Still, they accepted my steps among theirs.”

He spoke of what the elders never said, but what their silence allowed him to feel. “Walking with them, I began to know the grass on the plains and along the riversides, the trees in the forest and the lone acacia on the savannah. I came to know the dust, the way it carried our footprints like thoughts. The mud and sand made our footprints as imprinted memories of the walk. Dawn was divine, the first rays of the sun were hope. And the shade of the acacia, that was the abode of the ancestors, where we rested.”

He paused, searching for the word that might hold it all. “The feelings they gave me were of beauty,” he said at last, “and that beauty was peace. A good feeling in the body.”

He leaned back and closed his eyes for a moment. “That is what I write about in One Who Dreams Is Called a Prophet,” he said. “Of land as mother’s embrace, her lap — therefore peace.”

Then, in a near whisper, he added, “For Alama, walking restored harmony, and he knew who he was. My body opens with steps on the earth.”

The sentence lingered between us like a prayer.

The Pedagogy of the Elders

I asked him, “In One Who Dreams Is Called a Prophet, Alama’s walk is also an archive of elders. How did walking with them transform your understanding of knowledge and authority?”

“I began to understand that knowledge came from the seven senses the elders recognised,” he said, as if weighing the words in his hands before letting them go. “Walking was mostly in silence. Understanding was through the body, not through speech.”

He explained how the elders never pointed or instructed in the manner of teachers. “They would not say, ‘Look over there.’ Instead, they would gaze, and their eyes would take my eyes with them — to a distant feral animal keeping watch, to rain clouds gathering at the edge of the sky, to a thorny plant hiding at our feet.”

“That was how I learned the landscape, not as information but as a feeling and awareness. The world entered through the senses, quietly, as if by permission.”

To ask questions, he said, would have been an intrusion. “I did not learn about their histories directly. To ask would have been disrespectful. I listened instead, through silence. My field assistants, young men I had trained, knew how to ask as befitted their age and status. Through them, stories reached me later, carried across generations.”

He folded his hands and nodded slightly, as if acknowledging the patience that such learning requires. “Knowledge,” he said, “is sensual before it is cerebral. The elders taught me to know by feeling.”

He had already begun, by then, to question what his own presence meant. “I realised a researcher is an intruder,” he said. “White researchers used their colour and money. People tolerated them with a residue of colonial awe. I had to carry myself differently.” Today, he tells his doctoral students that the institutional ethics form is not enough. “They must write a second statement with the community,” he said. “It teaches them not to extract knowledge but to enter a shared moral field.”

He hesitated when I asked about authority. “I have no comment on elders’ authority at this moment,” he said finally, his tone neither evasive nor dismissive, only reverent. It was as if to speak of authority would itself disturb the delicate order of respect in which that authority was held.

The silence that followed was itself an answer. In it, one could almost hear the cadence of footsteps across dry grass — the sound of knowledge being passed, not by decree, but by rhythm.

I asked him what kinds of stories emerge only when one walks side by side, rather than sitting face to face.

“Whether we were sitting or walking,” he said, as if remembering the long, dusty roads of his youth, “stories were told according to how the elders perceived me, never at random. It was different with each one. Sometimes they shaped the story for who they thought I was, or for what they believed I could understand of their culture.”

He paused, letting the weight of that trust settle in the air. “The elders were cautious,” he continued. “You must remember the time, the decades after independence. There were conflicts, enmities with neighbouring groups. Suspicion travelled in the wind. To speak too openly was to risk being misunderstood.”

In those years, listening required a kind of humility, almost invisibility. “The stories of peace that I later wrote about, I learned through my field assistants,” he said. “They were able to hear what I could not. The elders spoke to them in their own time, when I was no longer an obstacle. Within families, the words could flow freely again.”

“I was never time specific. The story arrived when it was ready.”

There was a quiet wisdom in that — that knowledge cannot be extracted by schedule, that peace itself resists haste.

I asked how elders embody peace differently from how institutions or governments define it.

“Elders sense peace bodily,” he said. “Governments and institutions define it with formulas and policies handed down by the IMF and the World Bank, through our Western-educated officials and consultants, people who have not walked again since their school days.”

“Peace in the body,” he said, without bitterness, only with a kind of mournful clarity, “is not the same as peace on paper. Elders know the difference. They live it.”

The room fell silent again, as if the air itself understood.

This is part one of two part interview. Part two out soon.