The mountains, as a symbol of guerrilla resistance against the riyasat of Pakistan, have played a crucial part in the politics and life of Balochistan. “To take to the mountains” is a euphemism for starting or joining a guerrilla war. There have been at least six significant “takings to the mountains” since 1948. The first was that of Prince Abdul Karim, against the forced accession of Kalat State into Pakistan in 1948. The second was that of Nouroz Khan, against the administrative amalgamation of Balochistan with the rest of Pakistan in the 1950s. The third was that of Sher Muhammad Marri in the 1960s, for similar reasons. This was followed by a near-decade-long and highly organised rebellion of the Baloch People’s Liberation Front in the 1970s. The 1980s and 1990s were a lull for guerrilla warfare, but in 2006, Nawab Akhtar Bugti, head of the Bugti tribe, aggrieved by the dictatorship of Musharraf, again took to the mountains. His camp was bombed and he was killed. His death sparked a new wave of guerrilla movements that continue until today.

The precedent and rationale for taking to the mountains were set by Prince Abdul Karim – honorifically known also as the Agha. The royal title belies the truth of the conditions under which the Agha lived and struggled; he was a comrade who spent his life in political struggle for the rights of the Baloch and other oppressed groups. A prince far removed from jewels and the luscious life of the imaginary world of Arabian tales, he was more at home in prisons and with left-wing activists on the front lines of movements for the Baloch and for workers.

Abdul Karim was the younger brother of the Khan of Kalat. Having learnt that the Khan had acceded to Pakistan and that later Pakistan had annexed the Makran area administratively against the Khan’s wishes, he “disappeared” with some supporters and set out to camp in the mountainous area across the border from Balochistan, inside Afghanistan. While in camp, he sent a letter to his brother, the Khan of Kalat. It was intercepted by Pakistani intelligence agencies, translated, and later placed in the Balochistan Archive (a physical archive based in Quetta and managed by the Balochistan Provincial Government). From there, a former student of mine, Zaki Abbas, obtained a copy of the letter and about 1,000 other pages of archival material belonging to the Government of Pakistan on the Prince and his movement.

Most of the documents are repetitive intelligence reports noting the movements of activists and the actions taken by the Pakistani state to end his movement. Yet, by reading the state’s archive against the grain, we can tell the story of the Prince of the Mountains. I spread the photocopied archive across my desk and, in a frenzy, went through it with a highlighter.

I started with the prince’s letter to his brother. The letter establishes grievances of the Baloch that have been echoed for seventy years. The prince notes that the actions of the Government of Pakistan in Balochistan have made “everyone restless” and that freedom is at stake—and that the Baloch both understand and desire it. He writes:

“The desire for freedom is neither absurd nor an intricate question which requires the brain of Plato to understand it. It requires a natural feeling, and even the most simple nomad understands it. Its seizure has made everyone’s soul restless. Those who could reach here [to the rebellion camp] and those who stayed behind were also restless.”

He goes on:

“When I considered the policy of the Government of Pakistan, I at once arrived at the conclusion that it is free from every restriction. It respects neither the religion of Islam, nor the established law, nor manners. One may expect at any time every kind of religious, administrative, and personal evil from this sort of government. There were only two courses of freedom open: (1) either there should be so much power to defend one’s rights, or (2) to run away from its clutches. So, I crossed its border.”

Abdul Karim did not share the Khan of Kalat’s view of Jinnah and the emergent State of Pakistan. While the Khan hoped his financial and moral support of Jinnah and the Muslim League in the previous decade would be remembered now that Pakistan had come into being (he was to be disappointed), Abdul Karim was under no such illusion. He expressed his analysis of the nature of the State of Pakistan in his letter:

“There is nothing in the letter [that the Khan of Kalat had sent him] which could move me to abandon my ‘hijrat’ [migration]. Has the forcible accession of Kalat been cancelled? And the province of Mekran restored so that there could be some ray of hope in the darkness? If not, has any representation been made for the restoration of Kalat’s rights in order to soothe the wound of accession, so that I may see how flexible the ‘Punjabi fascism’ is? If not this nor that, but increase in military deployment, economic blockage, arrest of peaceful passersby, firing on them, and in the whole of the State the utterance of my name is an offense—then, in these circumstances which cause me worry, I am unable to return.”

The letter goes on to note that the Pakistani state will continue to rely on “imperialist forces and, at their instance, it will suppress by power of the sword the natural tribal [Baloch] demands.”

The pattern of the Pakistani state and Baloch resistance was already established in the first year of Pakistan’s existence. The prince’s analysis—that the Pakistani state is a state in the hands of “Punjabi fascists” who are usurping Baloch resources and territory—continues to be the position of Baloch nationalists. It is an accurate analysis of what some theorists call racecraft: in our context, an ethnic-based hierarchy for distributing power, wealth, and life that forms the organisational principle of the state. He also noted the connection between the new State of Pakistan and imperial forces (Britain and the United States), predicting that this connection would grow, with the Pakistani state serving as a conduit for imperial capital. Again, he was right. He also set the precedent for the Baloch response: taking to the mountains and guerrilla warfare.

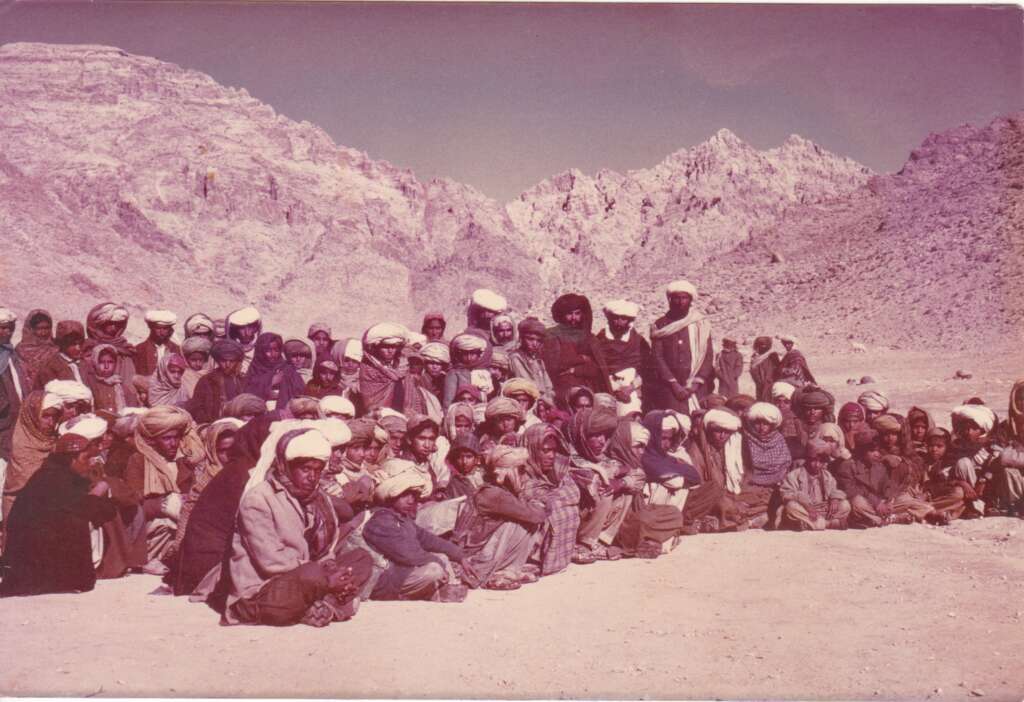

The documents provide insight into the counterinsurgency tactics of the Pakistani state against the Prince. Prince Abdul Karim set himself up in Sarlath, a few miles inside Afghanistan. His aim was to sit there and wait for people to join him. Many wanted to, but their path was blocked by a successful counterinsurgent operation by the Pakistani state.

The state, inheriting the power and techniques of British counterinsurgency, quickly began to dismantle support for Prince Abdul Karim. Ministers and “notables” sympathetic to his cause in Kalat were dismissed and exiled to Quetta, where they were kept under house arrest. In Quetta, intelligence officers watched them day and night, reporting on the people they met and the ideas they professed. Four platoons were requested by political agents in Balochistan to tackle the prince and were dispatched to block supply routes and stop those trying to join him. Government officials were sent to all notables and influential persons and, through bribes or threats, coerced them not to let people in their areas join the Agha, and to issue statements against him. Intelligence files record how four passes to Sarlath had check posts established to stop supplies and people reaching the camp. Meanwhile, political agents across Balochistan intensified efforts to identify and dissuade anyone attempting to support the prince logistically or otherwise.

Blocked from support within Kalat and Balochistan, the Prince turned to Afghanistan. He sent two emissaries to see what support might be possible. None was forthcoming. After two months of camping in Sarlath and nearby areas, the Prince decided to return to Balochistan and negotiate a return to Kalat with his brother. The Pakistani state was ready and waiting.

Once the Prince had entered Kalat, the Pakistani army surrounded his group and began an ambush. Abdul Karim’s men fired back and kept the army at bay. However, they were neither equipped nor intending to engage in a direct armed conflict. With injured men at camp and running out of supplies, including water, Abdul Karim agreed to come down from the mountains and return to Kalat. He was to be accompanied by the Wazir-e-Azam of Kalat State. The Wazir, however, was now subservient to the Pakistani state, so when the Prince came down with his men, it was not the Wazir but Brigadier Ahmad Jan and the Political Agent of Balochistan who met him. A government report notes: “They were disarmed and taken under escort to Kalat.” From Kalat, Abdul Karim was taken to Mach jail to be tried under the newly enforced Frontier Crimes Regulation.

Abdul Karim and 127 guerrillas who were with him were charged with “conspiracy to wage war against the State of Pakistan,” under Section 121-A of the Indian Penal Code and Section 12(2) of the Frontier Crimes Regulation. They were tried by a district magistrate and a jirga – rigged against them by Pakistani political agents. The mock trial – another precedent progressives of Balochistan have faced over the year – was only going one way. One hundred twenty-five of the accused were found guilty.

The intelligence report provides a summary of the sentences. It notes:

“The two ringleaders in the conspiracy, namely Abdul Karim and Muhammad Hussain Unqa, have each been sentenced to ten years’ rigorous imprisonment and substantial fines in addition. Of the remaining accused, three have been sentenced to seven years’ rigorous imprisonment each, eight to six years each, one to three years, twenty-seven to two years, and three to one year’s rigorous imprisonment each.”

In addition, all were fined and required to provide “security for future good behaviour.”

Abdul Karim was to remain central to progressive politics in the region. He was steadfast in his opposition to the militarist and fascist tendencies of the state and continued to fight for oppressed nationalities and classes in Pakistan. He opposed One Unit, joined with progressive forces in the National Awami Party, and struggled in and out of jail for equality among the nations that form Pakistan.

The guerrilla foco theory is attributed to Che Guevara and Fidel Castro. It argues that a small group of people can set up camp in the mountains and await others to join them, and that by visibly showing resistance and prefiguring future relations, they can win people over. Prince Abdul Karim argued for and acted out precisely this strategy a few decades before Che and Fidel. That remains his legacy. Taking to the mountains is a precise method of resistance, it is the syntax of resistance woven into Baloch history, by, among others, the Prince of the Mountains.