Most geniuses have one masterwork for which they are famous. For Che and Fidel, that work was surely the Cuban Revolution and its international humanism, just as it was for Lenin, the Russian. For CLR James, we can list “The Black Jacobins” as an extraordinary work of genius, as well as the underground Marxist group he co-led, known as the Johnson-Forest tendency. For Selma James and many other women of the 1970s Marxist Feminist movement, it was about recognizing the economic contributions of housework and children and establishing organizations that advocated for fair compensation for caring and reproductive labor. Their slogan, ‘invest in caring, not war’, remains the blueprint. For Spivak, it has been to chart a path for activism while working beyond Eurocentric Logocentrism.

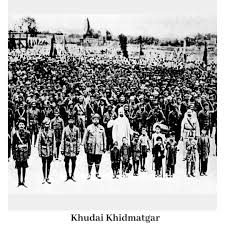

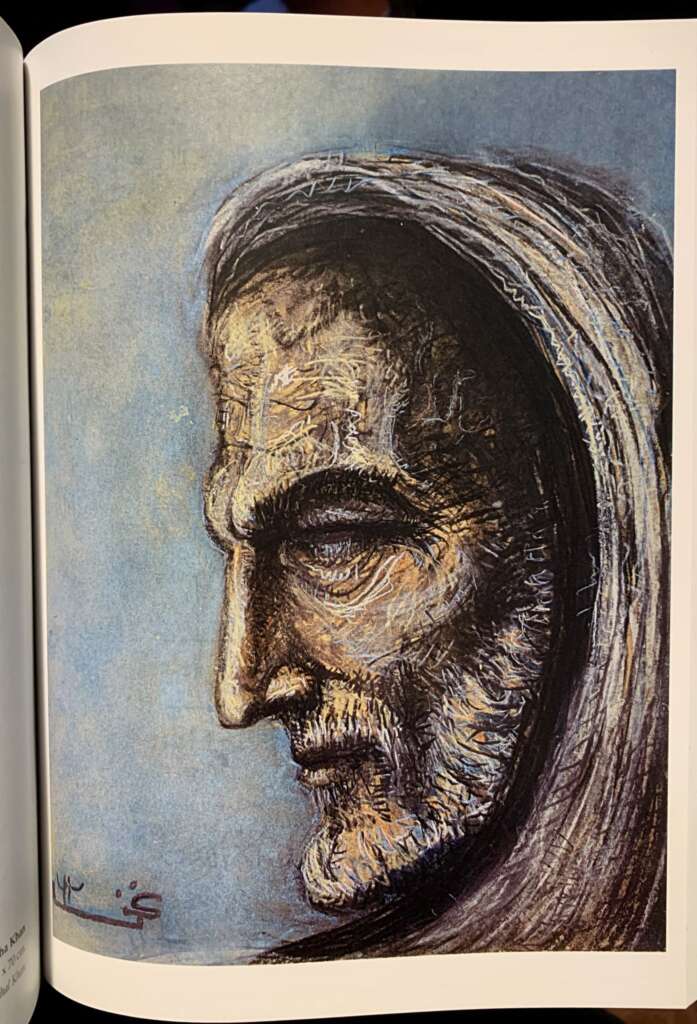

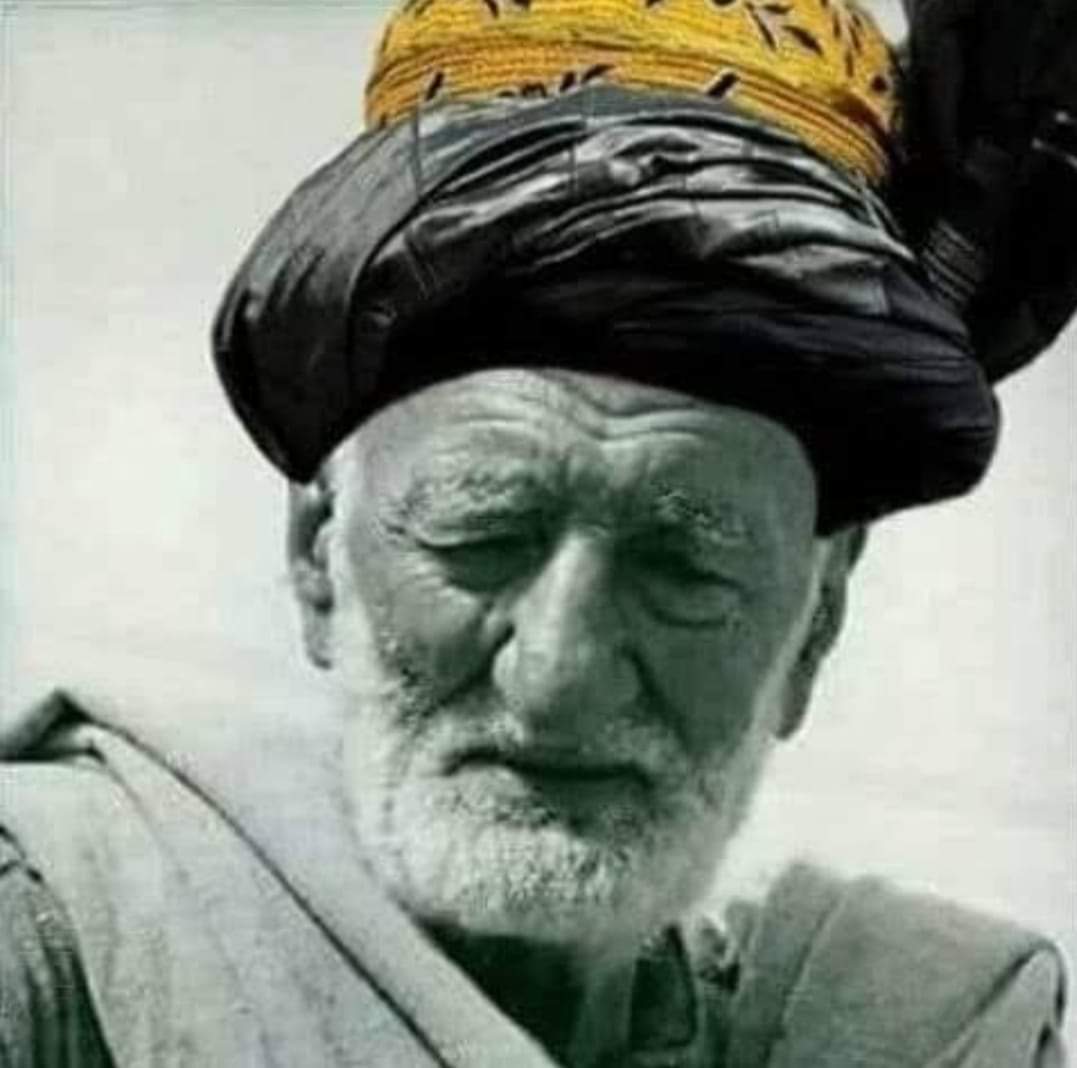

The list is long, but I never thought that a tall, six-foot-three, broad-shouldered, soft-spoken Khan from Utmanzai, Hashnagar, a mere graduate of King Edward’s School, Peshawar, would, before he turned 30, have three works of genius to his name. Abdul Ghaffar Khan, honorifically known as Badshah Khan (King of the Khans) and also Bacha Khan, a title bestowed upon him at the mere age of 27, created three masterpieces. In order of creation, they were: Anjuman-i-Islahul Afaghina (The Society for the Reform of the Afghan), Pakhtun magazine, and the greatest non-violent organization the world has yet known, the Khudai Khidmatgar. Here I want to write only of the first, Anjuman-i-Islahul Afaghina.

Bacha Khan was born in 1890; by then, the Pakhtun areas had been conquered, divided, and society had been socially engineered to serve the purpose of British imperialism.

The British did not arrive in the Pakhtun lands all at once but through stages. First, they inherited the Pakhtun lands that Ranjit Singh’s Sikh armies had earlier conquered. Singh had taken Attock in 1813 and Peshawar in 1823. The British gained control of these areas after the Treaty of Lahore in 1846 and solidified it by 1849. From that point, they gradually took over more Pakhtun areas. By 1879, they had control over Dir, Swat, Bannu, Khurram, and the Tirah Valley, and shortly after, they imposed the Durand Line, cutting the Pakhtuns off from their historical lands.

Once in military control, they set up a divide-and-rule administrative structure. Pakhtun regions were split into settled districts, tribal agencies, and the so-called “Frontier,” each governed by different laws and authorities. The Frontier Crimes Regulation of 1872 legalized collective punishment and institutionalized the state of exception, ensuring that Pakhtuns were doubly colonized – not only were they colonized like the rest of British India, but they were also subject to different laws compared to the rest of British India. This was made possible by ‘racecraft’ (a racial discourse upon which is fixed a governance structure of hierarchy), that discourse that even today follows Pakhtuns and renders them into non-being.

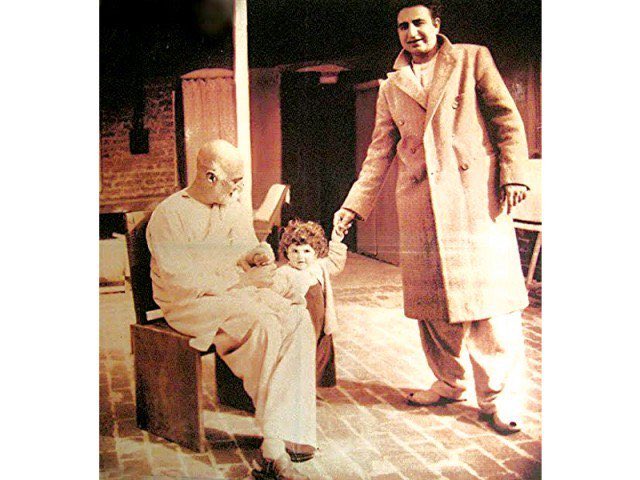

At the social and economic level, the British dismantled the egalitarian wesh system of land distribution, created loyal “big khans” through land grants, while peasants slipped into dependence. They also elevated mullahs, turning them into tools of propaganda to denounce reformers or neighbors as kafir. Ghani Khan, the great poet and Bacha Khan’s son, notes of them: “The colonial state supplied the tribes with divine-looking priests who perverted the tribesmen’s love of God into hatred of his brother.” Bacha Khan would oppose this colonial system.

Bacha Khan was born into a landowning family headed by Behram Khan, and was set on becoming a collaborator until he experienced racism firsthand. A friend advised him to apply for a commission in the British army. He did, was interviewed, approved, and on his way to a ‘good life’ – until he saw a British official mistreating a Sikh friend in a friend’s room and making it clear that the ‘darkies’ in the Empire would never be equal to whites. The experience of ‘racism’ or ‘racecraft’ led Ghaffar to give up on joining the British in any capacity. From that point on, he became a sworn enemy of British imperialists. Someone who understands their culture rejects the imperial ‘racial’ hierarchy that puts them down. Ghaffar Khan, unlike Gandhi, had no trouble rejecting the British idea of civilization and white superiority. He did so easily, already knowing from Pakhtun and Islamic history had contributions in science, art, poetry, and culture. He was not intimidated by an upstart ‘farangi’. His brother, studying in the UK at the time, arranged for him to join him, but Ghaffar Khan’s mother refused permission, fearing she would lose another son to foreign lands. Ghaffar stayed in his village with his mother, got married, and had two sons, Ghani and Wali Khan, while managing the family’s farmland. Ghani, in his book The Pathan, continues the story:

The young man [Bacha Khan] adored his wife-a whimsical, lovable,

generous creature, well-bred and from a fine old family.

But still he wandered. He worshipped his children, two

sons, but very often when he sat by the fire he would

stop cuddling them and a far-away look would come into

his eyes. His lovely wife knew these moods and hated

them. For every woman likes to possess all of a man.

She realized that there was something in this strong,

handsome husband of hers that made him forget her

beautiful eyes and the twitters of her children by the

fireside.

She did not live long to see those long silences and

dark moods tum into strength and action. She died

before she was twenty-five. They covered her with

flowers and took her to the burial ground in her wedding

robe. She left behind two baby boys with a bewildered,

terrified look in their eyes. They sensed the horror of

death though they did not understand or know what it

meant.

Abdul Ghaffar Khan’s restlessness increased. The

European war had brought to India a hypocritical promise of advance at its beginning and an influenza epidemic

in the end. He left his children in the tender care of

his old mother and drowned his sorrow in work and

Service.

He had found his profession in life. He had found a

new love-his people. Pathans must be united, educated, reformed and organised.

An educated Pakhtun was of no use to the British and today to the Pakistani state. His destiny for the empire is to be either a cheap soldier or collateral damage in drones, military operations, or other acts of the Pakistani state or imperial violence. In 1901-2, there were only 154 schools at all levels in the NWFP. Meanwhile, in Punjab, there were 2257, and Bengal had 45922. In 1911, only 25 males of 1000 could fit the criteria of literacy. The British saw the Pakhtun lands in India as a buffer zone, and rather than the pen, wanted Pakhtun children to have the gun and be susceptible to the ideas they whispered in the ear of paid mullahs. That way, they could be directed to fight at the whims of the British. The riyasat of Pakistan still uses this tactic, with their American backers, they want them as either Mujahideen or Taliban, but never educated and self-reliant. This tactic is now commonly known as the ‘mullah-military nexus’. For such a strategy to succeed, you must eliminate the ‘pen’ and educated people. That is precisely what the British attempted, but Ghaffar Khan had different ideas.

At first, Ghaffar Khan worked with the Haji of Turangzai on this. The title Haji refers to someone who has performed the Hajj. He was a popular preacher, educationalist, and anti-imperialist revolutionary inspired by Deoband. Photos of the Haji show a middle-aged man with a white beard and spectacles. Ghani noted that he was handsome, sturdy, and effectively violent in guerrilla warfare. In exile in the Mohammad Agency, he married a wealthy, beautiful widow who was drawn to his looks and also provided him with the material wealth to support his revolutionary zeal. After marriage, he performed the Hajj twice, and from then on, he looked and behaved as a religious man, just like Ghaffar Khan. The Haji was religiously educated and came from a nearby village of Ghaffar Khan’s in Charsadda. Like Ghaffar Khan, he wanted to end British rule and had joined a guerrilla war against the British in 1897 during his youth. That effort was unsuccessful, so he turned to social reform for a while. Along with Ghaffar Khan, he visited villages and preached for the construction of community and educational institutions, as well as unity among Pakhtuns. He established about 34 Azad Islamia Schools, which were set up in mosques. He urged Pakhtuns not to send their children to British missionary schools, but instead to Madrassa schools. Still in his 20s, Ghaffar Khan was honored with the title ‘Badshah Khan’ (the King of the Khans) for his anti-imperialist activities and social work with the Haji. At these schools, they preached anti-imperialism. The British, always watchful to keep a society ossified and scared of any element that brings life to society, acted in 1915, banned the schools, arrested the teachers, and searched for the Haji. He escaped to the tribal areas and remained there until his death. Ghaffar Khan now led the resistance with new tactics.

The Anjuman of Resistance

‘Today, The Pakhtun nation does not need the Gun, indeed they need the power of the pen. We want to take freedom of the country by pen rather than by guns.

Ghaffar Khan

Ghaffar Khan continued along similar lines as the Haji. He traveled on foot from village to village, met the people there, and worked to establish his first school: The Azad School of Utmanzai. The school was a collective effort. In the 1970s, Ghaffar Khan dictated an autobiography. Regarding the school, he writes: ‘We founded the Azad School Utmanzai in 1921, with the help of the Qazi Attaullah, Mian Ahmed Shah, Haji Abdul Ghaffar, Mohammad Abbas Khan, Abdul Akbar Khan Akbar, Tag Muhammad Khan, Abdullah Shah and Khadim Mohammad Akbar’.

I learned more about the school from the book ‘Bacha Khan’s Alternative Vision of Education’ by Dr. Mohammad Sohail Khan. I also had a phone conversation with Dr. Khan. He mentions that the school was set up in the house of Akram Khan, and boarding was set up in his guest house (Hujra). It was situated near Dhab Bridge, called Dhab pul in the local accent, at the entrance of the village of Utmanzai, coming from Charsadda. There were five classrooms initially, besides the three boarding rooms and an office for Anjuman in the building.

I decided to find the school and set out from Peshawar, which I was visiting at the time. Sohail Khan had told me that it no longer existed, but that its old location was opposite the shrine of Sheikh Jalal-e-Bukhari Baba. I headed to the shrine of Jalal-e-Bukhari Baba by car. I asked around for the shrine and was sent to it by locals. I parked the car and walked up to the shrine. It is a small shrine with little else but the saint’s grave and a sacred ancient tree rising at least 30 feet above it. I say ancient because, being confined within the shrine and therefore serving as a sanctuary of sacredness, it has survived at least from the time of Bacha Khan from defilement – there were few other large trees in sight. The shrine was adjacent to Tangi Road. The road is dusty but cooled by the nearby flow of the Jindi River and a smaller canal channel that flows a few hundred yards away. The school was opposite the shrine, so I crossed the street and now saw a mosque, commercial buildings, a sanitary store, many houses, and a general store. The area is littered with one-story commercial buildings with steel shutters at their front. What I was looking for was long gone. A few hundred yards further up the road, I found Quetta Chaye shop and went in, sat on a bright red plastic chair, and a similar red plastic table became my workstation. I ordered a paratha and a pot of cava, then I got out of my ransack. Dr. Sohail, A few hundred yards further up the road, I found Quetta Chaye shop and went in. I sat in a bright red plastic chair, and a similar red plastic table served as my workstation. I ordered a paratha and a pot of chai, then I took out Dr. Sohail Khan’s book from my bag and started learning about the school and the organization that was set up to run it.

Sohail Khan notes that to run the school and further the ideological work, Ghaffar Khan and his comrades founded the Anjuman-I-Islamhul Afghani (Society for the Reformation of Afghans). Bacha Khan, in his autobiography, notes the aims of the Anjuman: ‘We also established an Anjuman to create love, non-violence, nationalism, and to promote unity amongst Pakhtuns with the eradication of social evils’.

The Anjuman consisted of an advisory board of 50 members, which was to meet twice a month and bear the costs of the schools and the Anjuman. The members had to refrain from enmity with the people. They had to avoid using British courts of law and refrain from working for the British. They were asked to use and promote their native language. To this end, the Anjuman was constitutionally tasked with holding an annual poetic competition (Mushaira) in Utmanzai and covering the travel and other expenses of the poorer poets. The Anjuman also aimed to publish a newspaper in Pashtu. It was to have one president, two vice presidents, one general secretary, one assistant secretary, and one treasurer. The constitution established an inspector to oversee the schools and their examinations. The first meeting, many later meetings, and the annual poetic competition all took place on a vast ground outside the Azad school of Utmanzai, a few hundred yards from where I sat. At the inaugural meeting, leadership positions were allocated, and the membership also established three bodies: one to increase membership, another to disseminate their ideas, and a third to generate funds. The Anjuman, well organized, with funds and motivated by anti-imperialism, started off with zeal and never stopped.

At its founding, the school had 70 students, and Ghani was one of them. In an interview later in his life, he didn’t appreciate the conditions of the school. He was sent to it, as was his brother, Wali, because, I quote Ghani: ‘Father said that people would say he built a wretched school if he put his sons in a good school. That is why we attended this subpar school. What a horrible little school.’ Ghani was a boarder, and he notes that the classrooms were often turned into their bedrooms at night, and their bed sheets sometimes had scorpions in them. There was no toilet, and they would have to go outside for such matters. There was corporeal punishment for misbehaving, and the teachers were often mullahs with no passion and a danda (stick) in hand (for caning the children). Boarders paid 3 rupees per month, which was a small amount even back then, so the food they received was never enough. While Ghani considered it a ‘wretched place’, he understood why he was there. In the same interview, Ghani notes:

There was a crowd of them, and the Haji of Turangzai was one of them, my father was one of them, they were mostly priests [mullahs]. And they said that we have to educate the children to be anti-British from childhood. In [British] school they used to make us read … Ye Badshah Hamara [this King of Ours, a pro-British chant], this sort of thing. They said that from childhood they [the British] teach them loyalty and everything. But we should make a school where we can produce revolutionaries and workers. They made this one big school in our village and little schools here and there and everywhere, usually in the mosques.

He also notes that the headmaster was an idealist:

He had he left Aligarh [Muslim University] and had an M.A. He was the son of a Khan of Bannu [District in NWFP]. They were two brothers. They were all right, but the rest, we had mullahs and this religious education. There was no science because they could not afford it. And then there was my father’s usual economy. I mean, he used to sit on the ground!

The Anjuman consisted predominantly, at its founding, of members of the Khilafat movement. They were religious people, reformers, and anti-imperialists.

Ghani was not the austere saint that his father was, but he was the beneficiary of the revolutionaries. He didn’t like being in the ‘wretched’ school but understood why he was there and the message of the revolution his father worked selflessly for.

I called up Dr. Sohail to ask him about the school and Anjuman. Dr. Sohail Khan interviewed many of those who had attended the school and those who had been members of the Anjuman. I told him I could not find anything of the school building. He replied, ‘Yes, it isn’t there anymore, it was merged along with the rest of the 134 Azad schools that the Anjuman built into government district schools in 1946/7. The location was also changed; that land too was given by Ghaffar Khan. Look, the teachers were not paid too well, the aim was to get rid of the Farangi – when that end was met, these schools could be merged and the teachers could get better wages, a pension, and security of a government job.

What Professor, I asked, was the curriculum.

It was taken from Islamia College School, Peshawar, so you had English, Mathematics, History, Geography, Urdu, Islamiyah, and vocational subjects. Over time, it was refined, and technical knowledge was imparted. Skilled artisans were hired to teach the students such things as tailoring, hosiery, carpentry, cap making, and weaving. The school aimed to form students intellectually, technically, and morally. Co-curricular activities were essential for the last. The students had a weekly Bazmi Adab – a literary session. They also played sports. Football, Volleyball, and badminton were the most prominent sports. In fact, when Ghaffar Khan was arrested in 1921, he was busy preparing a football field for the students.

Ghaffar Khan continued to face arrests. First, in 1919, he was detained for six months for holding an assembly against the Rowlatt Bill, which granted oppressive powers to the police, but was still less harsh than the FCR, which applied in the NWFP. Bacha Khan had protested it in solidarity with the rest of India rather than for its impact on him and his people – FCR was applied in NWFP, so the Bill would not affect the Pakhtuns. Later, he was arrested again for founding the Azad Schools and sentenced to three years of hard labor. The chains were too small for him, and they cut into his ankles; in prison, he had to grind wheat daily, and he was mainly kept in solitary confinement. He endured his hardships patiently each time. In total, he spent about 37 years in jail out of his 93-year life. Despite his arrest in 1921, the schools continued to operate.

Every year, the school held an annual meeting. These were historic gatherings. The meetings openly discussed the financial affairs of the Anjuman, the progress of the schools, and their shortcomings. Students delivered speeches, recited poetry, and performed plays. Over the years, these events evolved, and attendance grew from hundreds to hundreds of thousands. By 1924, the meetings included daytime theater performances and nighttime national poetry competitions. Dr. Sohail recounted the 1927 gathering, saying,

That year Ghani gave a speech on the necessity of female education. Later, the students staged a play titled ‘Orphan’. The play aimed to portray society from the perspective of the oppressed and highlight the structures of power that enable their exploitation. The ‘orphan’ in the play receives no sympathy from the Khans. The mullahs offer no assistance and are shown to be more interested in profiteering than in helping the poor. The patwari (government land revenue official) is corrupt and offers no help to the orphan. The courts, controlled by the Khans, deny justice. Ultimately, the Pakhtun intellectuals are depicted as disconnected from the poor and the land, as their education alienates them from the people.

The play, by looking at society bottom up – the perspective of a poor orphan, demonstrates the sectors above the orphan and the need for change if justice were to return. After the play finished, later that evening, 100 or so poets recited their poems, and awards were given to the best poets. The following year, the play was again performed and was viewed by more than 50 000 people.

At this point, Dr. Sohail excitedly mentioned that Manmohan Singh, the former Prime Minister of India, had been a student at the school, ‘his father was stationed in Charsadda and he was looking for a place to send his son and knew that other Hindu and Sikh boys were studying at the school, so Manmohan was also sent here’. Not only that, but Nehru and Gandhi too had visited, given speeches, and spent time at the school – Nehru in 1937 and Gandhi in 1938.

Nothing but the glorious old tree over the shrine of Jalal-Bukhari Baba suggested the historical nature of the area I was sitting in.

Dr. Sohail went on:

The important intervention of these Azad schools was that they were the first school to impart education in the mother tongue, in Pashtu. The Anjuman was aware of the importance of taking charge of the curriculum. In my book, in chapter 6, I have summarized Ghaffar Khan’s view on education.

After our conversation, I turned to chapter 6 and found Ghaffar Khan’s views.

Ghaffar Khan tells us,

The illness of our nation is illiteracy. The prisons are full, the hanging ropes are worn out and the lands are confiscated. The slavery life makes us mourn every day. We are mourning every day due to slavery life, with new worries, hardships, hitches, complications and snags. We have not identified our disease, if made by someone, he hesitates to consult his physician

The Anjuman is institute purely for your service and reformation. If you assist the Anjuman, it will be able to serve you better. The present movement of Azad national education initiated by the Anjuman, is successful to a large extent. This phenomenal movement will enable you to stand on your own feet, strive for the autonomy, realize your self-esteem and encourage your will. It will enhance the passion for Islam, nation, tolerance and sacrifices.

The curriculum is in the hands of foreigners, it will enable you to obey their own agenda. It is producing the idle youth having no vocational training, moral integrity, ethics and nationalism.

…now imagine, if the government and education both are captive, how much the national will be degraded and demoralized. It is the intense need that we shall arrange education by our own according to our own needs to make the national self-reliable.

After my phone call with Dr. Sohail, I decided to walk a little and find something about the school and its grounds. I walked back to the shrine, crossed the road from it, and wandered further into the streets opposite. There were houses, steel shutter doors, garages, but nothing of the school or its grounds. Wandering around, I soon found myself next to a water channel that was merging into the Jindi River and a large, makeshift, lush green cricket ground. Maybe, I thought then, but now I am pretty sure, this was part of the grounds where thousands of anti-imperialists had gathered, where Badshah Khan had been arrested while busy creating a football pitch for students to play on, and where Ghani had first recited his poetry. I sat on the ground and reflected on what I had learned that day.

I began to realize that I knew little about decolonial history. I had believed that Fanon, Memmi, and Aimé Césaire were pioneers, and that decolonial concepts and ideas had become solidified through their work, which they wrote in the 1960s, while Bacha Khan was working on his anti-colonial pedagogy in the 1920s. While sitting by the water channel on the edge of what was once the Utmanzai Azad School, thinking of the writings of Ghani Khan and Ghaffar Khan. It struck me that the legacy of decolonial thought and action (praxis) passed through exactly this place. The idea I held dear – that Western-educated, metropolitan brown sahibs had returned to lead decolonial movements – didn’t hold up when faced with Hashnagar and the Anjuman. Ghaffar Khan and his many companions and co-creators were neither secular nor ‘Western’-educated. There’s nothing borrowed from Western thought in Ghaffar Khan. He refused to go abroad but, using indigenous practices and sources of knowledge—the Quran, Hadith, Islamic history, and Pakhtun culture—he developed an educational philosophy, an anti-colonial organization, and restructured Pakhtun society away from enmity and toward non-violence.

An educated, nonviolent, united population serves no interest for imperialists, which is why Ghaffar Khan chose these paths. He was a proud, strong Muslim farmer from Hashnagar, who knew neither Sartre nor the sophistication of cricket, as seen through the lens of CLR James, but he remains for us a decolonial thinker and activist of no small measure. It will take a few decades or more but in time Bacha Khan’s methods and works will set again the course for our future. Comparisons may be dull, but they motivate and guide us. So let me say it: Bacha Khan is not just the Khan of the Khans but the region’s greatest political genius.

1 Comment

Comments are closed.