“What can ‘art’ mean in a culture where the primary organ of perception is not the eye or the ears, but the heart? It requires a shift from the visible to the sensible, in which attention is directed not outwardly toward the object, but inwardly, within the heart.”

— Wendy M. K. Shaw, What Is “Islamic” Art? Between Religion and Perception. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2019, p. 8.

Contemporary Islamic art is currently undergoing a profound transformation, shaped by a convergence of historical legacies and contemporary sensibilities. This evolution is neither linear nor homogeneous. Rather, it is marked by a complex interplay of tradition, identity, modernity, and global politics. Artists working within or engaging with Islamic aesthetics today confront a dual challenge: to remain rooted in their cultural and spiritual heritage while also responding to the global contemporary art world’s conceptual and material demands. This tension is at the heart of current debates about the nature and direction of contemporary Islamic art.

Two influential texts that provide critical insights into these debates are Rasheed Araeen’s “Islam and Modernism” and Avinoam Shalem’s “What Do We Mean When We Say ‘Islamic Art’? A Plea for a Critical Historicization.” Together, they offer a rich foundation for examining the aesthetic, philosophical, and institutional challenges facing contemporary Islamic art. While Araeen critiques the colonial and Eurocentric frameworks that have historically marginalized Islamic expressions within modernist discourse, Shalem interrogates the very category of “Islamic art” itself, calling for a nuanced, historicized understanding that resists static definitions. This essay explores how their arguments illuminate the complexities and contradictions inherent in contemporary Islamic artistic practice and theorization.

Islamic Art and the Burden of Representation

The category of “Islamic art” is fraught with ambiguities and ideological baggage. Avinoam Shalem’s intervention is crucial here. He argues that Islamic art, as traditionally constructed within Western art historical discourse, is overly reliant on typologies and essentialist frameworks. Museums and academic institutions have long treated Islamic art as a monolithic category, defined more by religious or geographic provenance than by stylistic or conceptual coherence. This reductive framing freezes Islamic art in a pre-modern past, detaching it from the dynamic and pluralistic realities of Muslim societies today.

Shalem calls for a “critical historicization” that recognizes Islamic art as a fluid and contested field. He encourages scholars to move beyond static definitions and instead consider how artistic practices have been shaped by historical contexts, power dynamics, and cultural exchanges. This approach not only destabilizes rigid boundaries between Islamic and non-Islamic art but also foregrounds the agency of artists who navigate multiple identities and discourses. In doing so, Shalem opens up space for contemporary Islamic art to be understood not as a derivative or marginal tradition, but as an active site of cultural negotiation and innovation.

This reframing is particularly important in a globalized art world that often exoticizes or instrumentalizes Islamic aesthetics for market or political purposes. Contemporary artists of Muslim heritage are frequently expected to perform their “Islamic-ness,” whether through calligraphy, geometric abstraction, or references to religious texts. While some artists embrace these signifiers as a means of cultural affirmation, others resist or subvert them, challenging the very notion of what constitutes Islamic art. The expectation to produce recognizably “Islamic” work thus becomes a form of cultural containment, limiting the scope of artistic experimentation.

Wendy Shaw and the Perceptual Turn in Islamic Art

Adding a transformative layer to this critical discourse is Wendy M. K. Shaw’s perspective in her seminal book What Is “Islamic” Art? Between Religion and Perception. Shaw critiques the secular and Eurocentric paradigms that have long governed the study of Islamic art, proposing instead a decolonial methodology grounded in Islamic epistemologies. She argues that Islamic art must be understood through its own cultural and religious contexts—an art of perception that engages not only the intellect but the soul, the heart, and the senses. According to Shaw, Islamic aesthetics have historically emphasized inwardness and spiritual resonance, privileging the experiential over the merely visual.

This approach shifts the conversation from form and iconography to experience and reception. It opens up a framework in which Islamic art is not merely a static object of study but a dynamic field of spiritual and perceptual interaction. Shaw’s intervention aligns with Shalem’s call for critical historicization but goes further in suggesting that the very act of seeing must be rethought within Islamic contexts. As she notes, seeing in Islamic art is not neutral; it is ethically and spiritually charged. This recognition invites a more holistic, immersive engagement with Islamic art that transcends the rigid binaries of traditional versus contemporary, religious versus secular.

Araeen’s Challenge to Modernist Orthodoxy

In Islam & Modernism (2022), Rasheed Araeen’s essay provides a powerful critique of how modernism, particularly in its Eurocentric formulations, has marginalized non-Western artistic expressions. He argues that modernism’s claim to universality is deeply flawed, as it excludes the experiences and aesthetic traditions of colonized peoples. For Araeen, Islamic art must be understood not merely in relation to its formal properties but as a site of ideological struggle. The imposition of Western modernist values, he contends, has led to a crisis of identity among artists from Muslim-majority societies who find themselves caught between inherited traditions and the imperatives of Western art institutions.

Araeen is especially critical of how postcolonial artists are often required to conform to Western aesthetic norms in order to gain legitimacy. This demand produces what he terms a “mimicry of modernism,” where artists adopt the visual language of Western modernism without being allowed to fully participate in its intellectual or institutional frameworks. At the same time, attempts to assert a distinct Islamic modernism are often dismissed as parochial or anachronistic. This double bind reflects the broader structural inequalities of the global art system, in which Western centers continue to dictate the terms of recognition and value.

In response, Araeen calls for a radical rethinking of both Islamic art and modernism. He advocates for a dialogical approach that acknowledges the contributions of non-Western artists to modernism while also allowing for the development of indigenous modernities rooted in local histories and epistemologies. This vision aligns with Shalem’s call for critical historicization, as both scholars seek to decenter Western paradigms and affirm the legitimacy of alternative artistic trajectories.

Negotiating Identity and Authenticity

One of the central tensions in contemporary Islamic art is the negotiation of identity and authenticity. Artists must navigate a complex terrain in which their work is scrutinized not only for its aesthetic qualities but also for its cultural and religious “authenticity.” This scrutiny often stems from both Western audiences and internal community pressures. As a result, questions of who has the authority to define Islamic art, and what criteria should be used, become deeply contested.

Some artists respond to these challenges by embracing hybridity as a mode of resistance. They draw on a wide range of influences, from classical Islamic motifs to global pop culture, creating works that defy easy categorization. Others turn to traditional forms such as miniature painting or Sufi poetry, not as exercises in nostalgia but as means of reactivating dormant traditions within contemporary frameworks. In both cases, the goal is not to reproduce a fixed cultural identity but to explore its possibilities and contradictions.

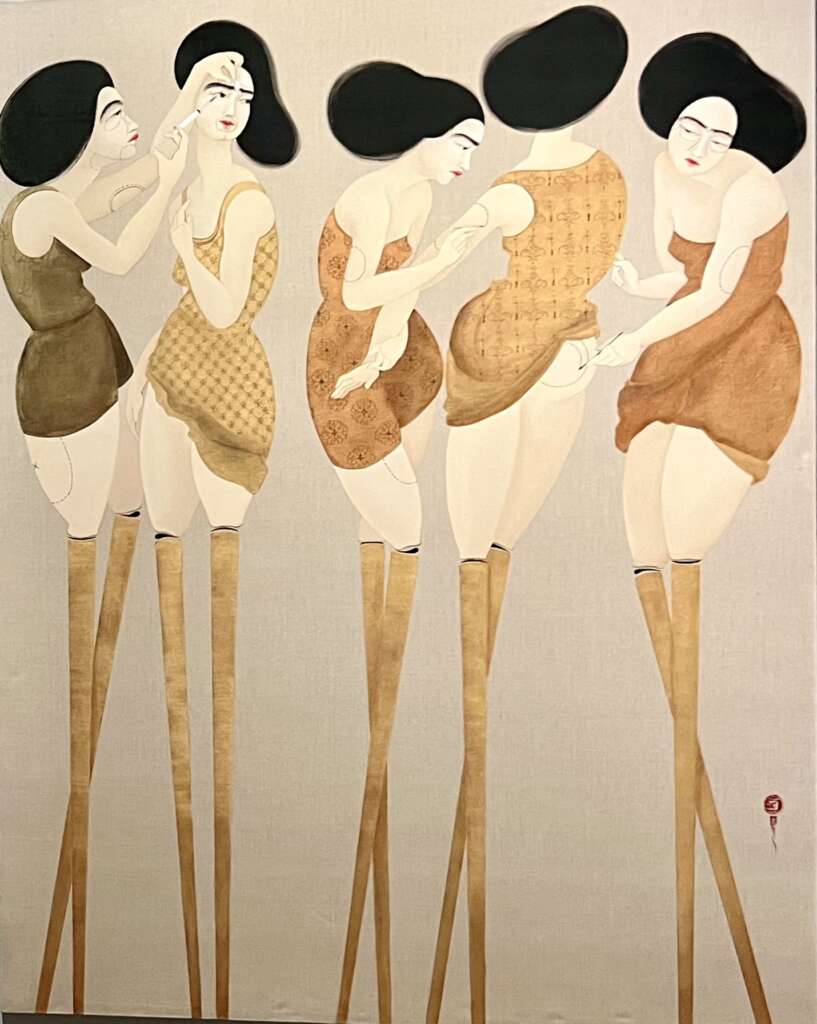

In contemporary Islamic art, women artists are not merely participants—they are conceptual agents redefining the visual grammar of faith, gender, body, and power. Whether rooted in the Islamic world or shaped by diasporic experience, these artists engage not in a return to authenticity but in a complex reframing of tradition. Their work questions the legitimacy of imposed binaries—secular vs. sacred, East vs. West, piety vs. feminism—and instead proposes a new, speculative space of representation. The work of Shirin Neshat and Shahzia Sikander has long exemplified this turn. Neshat’s haunting black-and-white portraits, layered with Farsi calligraphy, mediate the gaze between viewer and subject, speaking to both repression and inner resistance. Sikander’s subversion of Indo-Persian miniature painting creates densely referential fields where gender, empire, and authorship collide. Both navigate the visual codes of Islamic tradition not to preserve them, but to fracture and expand their possible meanings.

This conceptual intervention continues in the work of Egyptian Huda Lutfi, Turkish CANAN, and Iraqi-Swedish Hayv Kahraman, each of whom brings a distinct lens to the intersection of gender and Islamic visual heritage. Lutfi’s Hand of Silence juxtaposes ancient funerary portraiture with the Khamsa, invoking both death and protection, silence and voice. Her work becomes a site of embodied memory, where personal and civilizational histories overlap. CANAN’s Falname series stages a feminist divinatory practice, repurposing sacred texts to imagine new futures. It is both a re-enchantment and a critique, suggesting that destiny itself is a narrative open to revision. Kahraman, working from the fractures of war and displacement, renders the female body as archive—dissected, reassembled, and re-signified. Her stylized forms expose the violence of colonial gaze and aesthetic fetishization while reclaiming intimacy as resistance. What they offer is not a singular vision of “Islamic feminism,” but a plurality of embodied inquiries—each one both deeply situated and radically open.

Similarly, the Moroccan artist Hassan Hajjaj fuses Islamic aesthetics with street culture and fashion photography, challenging both Western stereotypes and local conservatism. These artists exemplify the dynamic and pluralistic nature of contemporary Islamic art, which resists essentialist definitions and embraces multiplicity.

Together, these artists articulate a language of Islamic art that is neither bound by tradition nor alienated from it. Their practices suggest that belonging is not a static identity but a continual negotiation. In this, they reorient Islamic art from a field of inherited meaning to one of critical generation.

Institutional Frameworks and the Politics of Display

The evolution of contemporary Islamic art cannot be understood in isolation from the institutional frameworks that shape its production and reception. Museums, galleries, biennales, and art fairs play a crucial role in determining which artists gain visibility and how their work is interpreted. In many cases, these institutions are guided by market logics or geopolitical agendas that influence the kinds of narratives that are promoted.

Exhibitions of Islamic art often oscillate between two extremes: either they present traditional artifacts in a historical vacuum, emphasizing their decorative or religious functions, or they showcase contemporary works as tokens of cultural diversity or political liberalism. Both approaches risk reducing Islamic art to a set of static signifiers or instrumentalizing it for ideological purposes. What is needed, as Shalem suggests, is a more critical curatorial practice that contextualizes Islamic art within broader art historical and sociopolitical frameworks.

Some institutions have begun to move in this direction. The Sharjah Biennial, for instance, has emerged as a significant platform for artists from the Islamic world and the Global South more broadly. Its curatorial approach often challenges Western-centric models by foregrounding local histories, collaborative practices, and experimental forms. Similarly, initiatives such as the Museum of Contemporary African Art Al Maaden (MACAAL) in Marrakech seek to create spaces where Islamic and African identities intersect in complex and generative ways.

One particularly illuminating example of this shift is the Islamic Arts Biennale in Saudi Arabia, as discussed in the Afikra Podcast episode featuring HE Rakan Altouq and Dr. Julian Raby. The biennale, staged in a historically conservative and religiously symbolic context, seeks to reframe Islamic art through a contemporary lens, foregrounding both continuity and innovation. Dr. Raby emphasizes that the exhibition aims to present the “richness and diversity of Islamic arts and culture,” moving beyond static categorizations to showcase Islamic art as a dynamic, living tradition.

HE Rakan Altouq underscores the importance of the biennale’s location in the historic Hajj terminal in Jeddah. He describes it as “a place that already speaks volumes about the Islamic experience of movement, of transition,” and as a powerful metaphor for the Biennale’s curatorial theme: “وما بينهما (And all that is in between).” This theme, according to Altouq, is intended to reflect the continuity between the sacred and the contemporary, the spiritual and the mundane, suggesting that Islamic art is not confined to historical forms but is embedded in a continuum of experience and expression.

These insights align with the broader themes discussed in this essay, particularly the need to critically historicize Islamic art and challenge Eurocentric narratives. The Biennale’s approach resonates with Avinoam Shalem’s call for a nuanced understanding of Islamic art that acknowledges its fluidity and contextual diversity. It also echoes Araeen’s insistence on the need to rethink institutional frameworks and empower non-Western narratives within global art discourse.

However, as with any state-backed cultural initiative, it is important to interrogate the politics behind the project. The Biennale also functions within a state-driven narrative of modernization and soft power. While its conceptual and curatorial innovations are significant, they exist within a larger framework that reflects Saudi Arabia’s attempt to position itself as a leader in cultural diplomacy. The risk remains that even the most progressive platforms can be co-opted into national branding strategies, complicating the authenticity and autonomy of artistic expression.

The issue of figural representation continues to animate debates in Islamic art discourse, as exemplified by recent controversies such as the dismissal of Erika López Prater from Hamline University. As Zainub Verjee details in her article “Image in Islam: La Longue Durée,” the complexity of image-making in Islamic traditions resists simplistic binaries of prohibition and permissibility. The tendency to reduce the history of Islamic figural representation to conservative doctrinal bans ignores centuries of rich visual culture where prophets and religious figures were depicted in nuanced, context-dependent ways.

A professor of Islamic art at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Christiane Gruber, asserts the need to recognize the “lost history” of imagining the Prophet Muhammad in Islamic cultures. The inclusion of veils and halos in medieval depictions were not acts of blasphemy but part of a symbolic lexicon that reflected theological subtleties. A leading scholar in Islamic art, Gruber emphasizes, “now more than ever, a rigorous study of such Islamic paintings proves necessary – and indeed vital – at a time of sharp debates over what is, or is not, Islamic.” This resonates deeply with broader calls in the field for historic and contextual literacy rather than reactive censorship.

Verjee’s analysis also situates the image debate within contemporary institutional and pedagogical contexts. The conflation of figural representation with Islamophobia or disrespect, especially within diversity and inclusion frameworks, risks flattening Islamic art history into a monolith dominated by the most austere interpretations. As Amna Khalid warns, this represents “a most extreme and conservative Muslim point of view,” privileging it as normative while sidelining more pluralistic perspectives. This concern is amplified in educational settings where precarious academic labor and administrative overreach stifle nuanced discourse in favor of risk-averse consensus.

Taken together, these insights underscore the importance of approaching figural representation in Islamic art not as a binary issue of offense versus freedom, but as a site of layered historical, theological, and aesthetic negotiation. Contemporary Islamic art and its institutions must reckon with this longue durée of image politics, embracing rather than evading its contradictions. Only then can we foster a curatorial and pedagogical ethos that respects diversity within Islamic thought and affirms the role of art as a space for critical inquiry and cultural continuity.

Inhabiting the Tensions, Reimagining the Sacred

The evolving field of contemporary Islamic art, as examined through the lenses of Araeen, Shalem, Shaw, Gruber, and Verjee, reveals the urgent need for a paradigm shift—one that neither reduces Islamic art to nostalgic traditionalism nor co-opts it into the demands of a homogenizing global modernity. The task is not to resolve the contradictions between faith, form, identity, and expression, but to make space for those contradictions to be actively negotiated, rearticulated, and represented.

Islamic art must be reclaimed as a dynamic space of perception, spirituality, critique, and resistance. It must reflect the diversity of Muslim experiences and the complexity of their histories without succumbing to essentialism or institutional tokenism. This means fostering intellectual and artistic environments that are bold enough to embrace debate, grounded enough to honour tradition, and expansive enough to allow for evolution.

In its most generative form, contemporary Islamic art challenges not only the viewer’s assumptions, but the very structures of knowledge and authority that shape what counts as art in the first place. It is in this spirit of reflexive plurality that Islamic art must continue to evolve—not as a reconciled category, but as a restless and revelatory force within the global cultural landscape.