Béla Tarr’s films transformed slowness into an ethical demand. Refusing narrative relief and political optimism, he made endurance of time, history, and looking the condition of cinema itself.

“There is no way out.”

—László Krasznahorkai, The Melancholy of Resistance, trans. George Szirtes (New York: New Directions, 1998), passim.

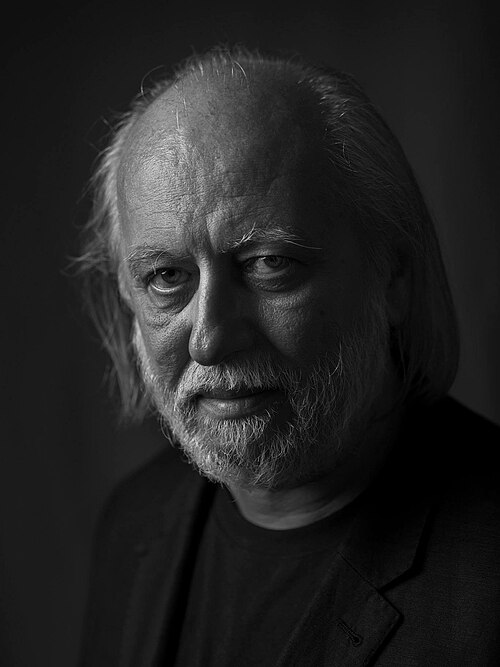

There are filmmakers whose deaths feel like the closing of a career, and there are others whose passing registers as the extinguishing of a climate. Béla Tarr (21 July 1955 – 6 January 2026) belonged unmistakably to the latter. His cinema did not merely tell stories or even articulate ideas; it created weather, an atmosphere of moral pressure, historical fatigue, and existential attrition in which viewers were asked not to watch so much as to endure, to dwell, to remain. With his death, a certain ethical possibility of cinema, one that refused velocity, consolation, and transcendence, withdraws further from an already accelerating world.

Tarr’s work was never large in volume, but it was vast in implication. Over roughly three decades, he fashioned a body of films that insisted on duration as a moral stance and slowness as a form of resistance. In an era increasingly governed by circulation, distraction, and spectacle, Tarr made films that were obstinately heavy: heavy with time, with weather, with history’s residue. To encounter them was to submit to a cinema that did not flatter the viewer’s intelligence or soothe their impatience, but instead tested the limits of attention itself.

Béla Tarr and the Hungarian Trinity of Endurance

Béla Tarr stands at the visual and ethical centre of a distinctly Hungarian trinity, formed with the writers László Krasznahorkai, 2025 Nobel Prize in Literature laureate, and Péter Nádas—three figures who did not merely respond to the collapse of twentieth-century political certainties, but developed enduring forms capable of surviving their aftermath. If post-communist Hungarian culture produced a grammar of persistence without consolation, it is here, and Tarr is its most publicly legible articulation: the figure through whom this sensibility became visible, temporal, and inescapable.

Nádas internalises the apocalypse. In A Book of Memories and Parallel Stories, catastrophe arrives not as event but as inscription. History burrows inward, embedding itself in sensation, shame, erotic memory, and corporeal reflex. His prose is forensic, fragmentary, and morally exacting—a sustained act of perceptual ethics. For Nádas, the body is an archive, and memory is not salvific but contaminating: something borne unwillingly in nerves and gestures. Apocalypse, in his work, is intimate.

Krasznahorkai externalises this condition into syntax and movement. His sentences stretch towards exhaustion, refusing closure, circling themselves like thought trapped in an administrative labyrinth. His landscapes—mudflats, abandoned collectives, provincial ruins—are not backdrops but conditions of existence. Time in Krasznahorkai does not progress; it accumulates. Meaning is never resolved, only delayed, degraded, and redistributed across endless motion.

Tarr, however, renders this metaphysics unavoidable. Where Nádas inscribes collapse into flesh, and Krasznahorkai disperses it across language, Tarr gives it duration, weight, and weather. From Damnation (1988) through Werckmeister Harmonies (2000), he translates Krasznahorkai’s long sentences into unbroken camera movements, making time itself the primary material of cinema. His films do not interpret despair; they stage it as lived experience. The camera lingers not because revelation is imminent, but because there is nowhere else to go. Endurance is no longer metaphorical; it is demanded.

What unites this trinity is not theme but method. Each insists that fidelity to the real requires resisting narrative release, psychological relief, and historical optimism. Their shared refusal of redemption is not nihilistic but exacting. In an age that promises constant novelty and emotional throughput, their most radical gesture is to remain with what is already known, already failing, already exhausted.

Their Hungary is not merely post-Soviet; it is post-redemptive. And yet art persists—not as salvation, but as attention. In Tarr’s cinema especially, attention becomes a moral discipline: the willingness to stay with time after meaning has withdrawn.

From social realism to metaphysical ruin

Tarr’s early films emerged from the particular political and social conditions of late socialist Hungary. Works such as Family Nest (1979), The Outsider (1981), and The Prefab People (1982) are often grouped under the label of social realism, but this description risks understatement. These films already display Tarr’s defining preoccupation: the way structural forces grind down individual lives not through dramatic catastrophe, but through accumulation, repetition, and administrative indifference. Shot with handheld cameras and featuring non-professional actors, they depict housing shortages, marital breakdowns, alcoholism, and the petty humiliations of working-class life. What distinguishes them is not merely their sociological acuity, but their refusal of redemption. Their social realism usually gestures towards reform; Tarr’s early films already doubt that repair is possible.

This scepticism deepened as Tarr’s style transformed. With Damnation (1988), his cinema underwent a decisive shift. The handheld immediacy gave way to monumental long takes; the social world dissolved into a metaphysical landscape of rain, mud, and industrial ruin. Plot thinned to a skeletal outline, while mood thickened into an oppressive density. It was here that Tarr discovered the formal grammar that would define his mature work: black-and-white cinematography, choreographed camera movements, and a rhythmic structure that foregrounded repetition over progression.

Crucially, this stylistic turn was not an escape from politics but a reconfiguration of it. Tarr was often described as a pessimist, even a nihilist, but such terms misunderstand the political intelligence of his cinema. What his films register is not despair as mood, but despair as condition—a historically produced exhaustion in which traditional political categories have lost their efficacy. In Tarr’s world, ideology no longer mobilises, revolt no longer coheres, and hope itself has become suspect, easily manipulated by demagogues and charlatans.

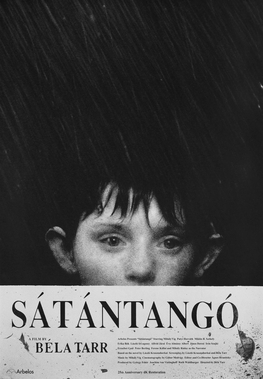

The apocalypse of waiting: Sátántangó

This diagnosis reaches its most exhaustive articulation in Sátántangó (1994), Tarr’s monumental adaptation of László Krasznahorkai’s novel. Running over seven hours and structured in a palindromic movement of twelve chapters, Sátántangó is less a narrative than a temporal ordeal. Its setting, a collective farm collapsing in the aftermath of socialism, serves as a microcosm for a society unmoored from both ideology and future.

The film’s notorious length is not an aesthetic provocation for its own sake. Duration in Sátántangó functions as an ethical instrument. By extending scenes far beyond narrative necessity—peasants trudging through mud, cows wandering through abandoned buildings, villagers drinking themselves into stupor—Tarr forces the viewer to inhabit the same temporal stagnation as his characters. Nothing happens, and this nothingness is the point. History, the film suggests, does not always move through decisive breaks; it often rots in place.

The figure of Irimiás, the false messiah who promises renewal while delivering only further subjugation, embodies Tarr’s bleak political insight. Hope, once detached from material transformation, becomes a technology of domination. The villagers’ willingness to believe is not mocked, but mourned. Sátántangó does not condemn faith as such; it exposes the conditions under which faith becomes a trap.

Stylistically, the film announces Tarr’s complete mastery of cinematic time. Long takes unfold with a grim inevitability, choreographed to the mournful repetitions of Mihály Víg’s score. The camera does not observe from a distance; it follows, circles, waits. This movement generates a peculiar intimacy, one that refuses psychological access while insisting on physical proximity. They remain opaque, worn down to gestures, habits, silences.

Order, violence, and the cosmic farce

If Sátántangó is Tarr’s epic of collapse, Werckmeister Harmonies is his parable of order and violence. Set in a provincial town disrupted by the arrival of a mysterious circus, the film pivots around two symbolic figures: a colossal whale and a shadowy Prince whose speeches incite unrest. At the centre stands János Valuska, a naïve and gentle soul whose belief in cosmic harmony renders him incapable of understanding the brutality unfolding around him.

The film opens with one of Tarr’s most celebrated sequences: an extended tracking shot in which drunken townsmen reenact a solar eclipse in a bar. It is a scene of grotesque beauty, at once comic and ominous, that encapsulates the film’s central tension between cosmic order and human chaos. Tarr stages the universe as choreography, but history as riot.

The mob violence that erupts midway through the film—culminating in the infamous hospital sequence—is among the most devastating moments in modern cinema. Shot in a single, unbroken take, it follows a crowd as it storms through empty corridors, smashing equipment and terrorising the vulnerable. When the mob encounters a naked, emaciated old man, its fury collapses into shame. Violence exhausts itself not through justice, but through exposure to fragility.

Politically, Werckmeister Harmonies marks Tarr’s most explicit engagement with the mechanics of authoritarianism. The Prince is less a character than a function: a voice that mobilises resentment without content, a precursor to the hollow populisms that would later proliferate across Europe and beyond. Tarr does not offer analysis in the conventional sense; he offers anatomy. Power, in his films, operates less through ideology than through affect—fear, humiliation, longing. Power in Tarr is hollow, yet effective precisely because it demands nothing except endurance.

What Tarr achieved here was not simply a synthesis of literary and cinematic modernism, but the transformation of a distinctly Hungarian sensibility into an ethical experience of time, one that viewers were compelled to inhabit rather than interpret.

With The Turin Horse, Tarr announced not only the end of his filmmaking career but, in some sense, the end of his cinematic world. Inspired loosely by an anecdote about Nietzsche witnessing the beating of a horse, the film reduces existence to its barest elements: a father, a daughter, a horse, a wind-swept plain. Over six days, we watch as routine disintegrates. The horse refuses to move. The well dries up. The light fades.

What distinguishes The Turin Horse is not its austerity alone, but its radical refusal of explanation. There is no allegorical key that unlocks its meaning, no philosophical thesis that resolves its images. Instead, Tarr presents entropy as lived experience. The film’s repetitions—dressing, eating, staring into the void—are not symbolic gestures but the very substance of life as attrition.

If Sátántangó is about false beginnings and Werckmeister Harmonies about corrupted order, The Turin Horse is about endings without revelation. It offers no apocalypse, only exhaustion. In doing so, it stages a devastating critique of modernity’s faith in progress. History does not culminate in redemption or catastrophe; it simply runs out.

Tarr’s politics: beyond slogans and systems

Tarr resisted political labelling, and for good reason. His films do not align comfortably with any programmatic ideology. Yet to describe him as apolitical would be a grave error. His politics are embedded not in statements but in structures, in the way time is organised, bodies are positioned, and futures are foreclosed.

At heart, Tarr was a filmmaker of systemic violence, not the spectacular violence of war or revolution, but the slow, grinding violence of abandonment, neglect, and bureaucratic indifference. His cinema exposes how political systems persist even after their ideological justifications have collapsed. Late socialism, post-socialism, neoliberalism are not treated as distinct epochs, but as variations on a condition in which power has become impersonal and suffering normalised.

Tarr’s deep suspicion of hope is often misread as cynicism. In fact, it is ethical rigour. He understood that hope, when abstracted from material change, can function as an anaesthetic. His films do not abolish the possibility of ethics; they relocate it. Ethics, in Tarr, emerges not from belief in a better future, but from attention to the present—to bodies, gestures, durations that refuse to be optimised or erased.

This commitment extended beyond his films. In his later years, Tarr devoted himself to teaching, founding the film.factory in Sarajevo, where he mentored young filmmakers from around the world. His pedagogy emphasised responsibility over style, insistence over novelty. Cinema, he argued, was not about expression but about obligation: to time, to reality, to the dignity of the image.

Legacy in an age of speed

To speak of Tarr’s influence is to confront a paradox. He is revered, cited, canonised, and yet his cinema stands in stark opposition to the dominant logics of contemporary image culture. In an age of algorithmic recommendation and accelerated consumption, Tarr’s films are almost unprogrammable. They demand conditions—silence, patience, endurance—that our platforms actively discourage.

And yet, precisely for this reason, his legacy endures as a form of resistance. Tarr reminds us that cinema can still be a site of ethical encounter, not merely a vehicle for content. His films insist that looking is a moral act, that attention is finite and therefore precious.

If Krasznahorkai gave late modern despair its syntax and Nádas its corporeal depth, it was Tarr who rendered it unavoidable, who made endurance itself the condition of spectatorship.

Béla Tarr leaves behind no school and no method easily transferred. What he leaves is more severe: a standard of attention calibrated to a world that no longer explains itself. His films do not argue. They persist. They ask not what history means, but how long one is willing to remain with it after meaning has thinned out. If others gave this condition its language or its interior depth, it was Tarr who gave it time, who made endurance itself the measure of looking. When the light finally fades in The Turin Horse, nothing is resolved. What remains is duration, and the obligation to have stayed.

To have made such a cinema is not a small achievement. It is a moral one.

Narendra Pachkhédé is a critic and writer who splits his time between Toronto, London and Geneva.