Mohammad Bakri’s death marks more than the loss of a major actor and filmmaker. It exposes the conditions under which Palestinian cinema has been forced to exist.

“Even the dead will not be safe from the enemy if he wins.”

— Walter Benjamin, Theses on the Philosophy of History (1940), Thesis VI

The death of Mohammad Bakri (1953-2025) does not submit easily to the conventions of obituary writing. It is not an event that closes a chapter so much as one that exposes a condition. This is not an attempt to survey Palestinian cinema as a field, but to take measure of what stands to be lost when a life like Bakri’s disappears from it. Bakri’s passing compels a reckoning not only with an individual career of unusual courage and clarity, but with the precarious ecology in which Palestinian cinema has long been made, unmade, confiscated, reassembled, and forced to begin

Bakri mattered not because he symbolized Palestinian cinema, a role he would have rejected, but because his life and work clarified what it has meant to practice cinema, theatre, and public speech under conditions that deny permanence to image, voice, and archive alike. His death marks the loss of a singular ethical presence, but also sharpens our understanding of a field whose instability is not accidental but structural.

The Face as an Ethical Register

Bakri’s significance as an actor was never reducible to range or transformation in the conventional sense. What distinguished him was calibration. His performances were marked by restraint, by an intelligence acutely aware of how easily Palestinian suffering could be consumed as spectacle. He refused that economy. Grief in his work was disciplined rather than displayed. Anger was lucid rather than eruptive. Silence carried pressure.

This restraint was not aesthetic minimalism but a moral position. In a representational field that routinely demands Palestinians perform injury as proof of authenticity, Bakri insisted on dignity without exhibition. His face carried history without theatricalizing it. It held irony, fatigue, and resolve in equal measure.

This ethic extended beyond performance into the existential choices that shaped his life. When asked in an interview whether he would ever leave Palestine, Bakri replied: “I’d never leave, no. If they decide to leave though, I wouldn’t be sad”. The remark is revealing for its refusal to submit to moral coercion. Staying is not elevated into virtue, nor leaving cast as betrayal. It is a commitment assumed without demanding sacrifice from others.

In endangered live theatre, this ethic acquired an intensified materiality. To stand on stage under surveillance and threat was not a metaphor; it was a risk. Theatre became civic endurance, a practice of presence in which absence often served as the governing logic. Bakri treated the body itself as an archive that could be assaulted, constrained, and disciplined, but not fully confiscated.

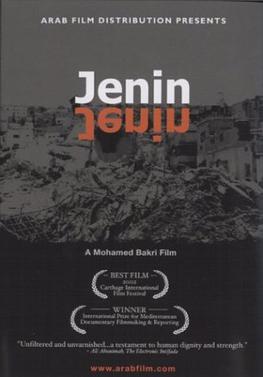

Jenin, Jenin, and the Juridical Capture of Testimony

Bakri’s most consequential intervention remains Jenin, Jenin (2002). The film has been repeatedly described as controversial, banned, or censored, yet such terms obscure its deeper provocation. Jenin, Jenin does not argue in the language of investigation or adjudication. It assembles testimony. It listens. It allows voices to remain fractured, contradictory, unresolved.

This refusal of narrative arbitration is precisely what rendered the film intolerable to dominant regimes of credibility. Palestinian testimony is routinely treated as excessive, partisan, or unreliable unless it submits to externally imposed grammars of verification. Bakri refused that submission. He did not ask for testimony to mimic the court or the commission. He exposed those forms as already ideological.

Bakri was acutely aware of the burden placed on Palestinian performers long before Jenin, Jenin. Reflecting on his role in Costa Gavras’s Hanna K. (1983), he once remarked that assuming such responsibility felt “like carrying a cross on my shoulders”. The phrase is telling less for its drama than for what it anticipates: the expectation that Palestinian actors bear history, grievance, and proof simultaneously, often within hostile narrative frameworks.

Given the circumstances of Jenin, Jenin’s production must be stated without euphemism. Bakri survived the shoot. Other members of the crew were assassinated. This is not a tragic context. It is a constitutive condition. Palestinian images are often produced under lethal threat. Filming itself becomes a provocation.

At its most elemental, Jenin, Jenin is a film composed of testimony. Bakri entered the Jenin refugee camp in April 2002, shortly after the Israeli military assault and withdrawal, at a moment when international journalists had been largely denied access. What the camera records are not strategic accounts or forensic reconstructions, but the voices of residents standing amid ruins. Men, women, and children speak directly to the lens about what they witnessed, lost, and survived. The film remains resolutely modest in method. There is no omniscient narration, no balancing authority, no external verification. Testimonies accumulate without adjudication. Contradictions are left intact.

This formal restraint is not an aesthetic limitation. It is the film’s ethical claim. Jenin, Jenin refuses the demand that Palestinian speech first submit to the custodial frameworks of military investigation, judicial review, or liberal media arbitration in order to count as truth. The camera listens rather than proves. Palestinian civilians appear not as objects of humanitarian concern, but as speaking subjects whose accounts do not require authorization.

It is precisely this refusal that defines Bakri’s struggle as a filmmaker. As the legal and cultural campaign against the film later demonstrated, the controversy was never fundamentally about a factual dispute. The film was reclassified as defamatory not because its claims were disproven, but because it presented Palestinian testimony outside Israeli institutional mediation. Testimony was converted into injury. Witness became a liability.

The lawsuit brought years later by an Israeli soldier made this logic explicit. The courts did not need to revisit the destruction of the camp, the civilian deaths, or the asymmetry of force. These matters were rendered legally irrelevant. What mattered was reputational harm. Palestinian memory was subordinated to the symbolic protection of the state. Censorship thus proceeded without naming itself, cloaked in the procedural language of liberal law.

In this sense, Jenin, Jenin marks a decisive threshold in Palestinian cinema. It exposes the invisible line between tolerated representation and inadmissible testimony. Bakri understood that the demand placed upon him was not for correction or balance, but for submission. His refusal to retract or apologize was not obstinacy. It was clarity. He had crossed a line that Palestinian cinema is not permitted to cross without consequence, and in doing so, revealed where that line lies.

The film’s afterlife mirrors this condition. It is repeatedly taken down and reuploaded. Its circulation is fragile, interrupted, and dependent on collective retrieval.

Bakri later articulated the structural nature of this struggle with characteristic clarity: “I realised that my Palestinian narrative can never be accepted by an Israeli filmmaker, no matter how progressive and liberal they are.” This insight cuts to the heart of the matter. The problem is not censorship alone, but asymmetry. Liberal inclusion remains conditional. Palestinian speech is tolerated only when it conforms to pre-existing grammars of intelligibility.

Genealogies of the Interrupted Image

Bakri’s work emerges from a longer, fractured genealogy of Palestinian cinema, one that begins with the militant image-making of the post-1967 period. Films such as Palestine in the Eye by Mustafa Abu Ali conceived cinema as an extension of revolutionary praxis. The image was declarative. It asserted the right to narrate without permission.

Yet the fate of this cinema reveals the structural condition that followed. Many of these films were lost, seized, or rendered inaccessible. The revolutionary image did not merely fail politically. It was actively interrupted. What followed was not a smooth transition into reflective post-revolutionary cinema, but a prolonged condition of suspension.

The shorts curated under Provoked Narratives, spanning 1967 to 1984, testify to this urgency. These films prioritize risk over preservation. Their existence is provisional. They were made to circulate quickly, often clandestinely, without expectation of longevity.

Bakri belongs to the generation that inherited this rupture. His work does not attempt to resume revolutionary teleology. It accepts interruption as a historical condition.

The Archive as a Scene of Power

The fate of Jenin, Jenin makes visible only the most immediate layer of a much deeper architecture of control. What Bakri confronted through litigation and censorship was not simply hostility to a single film, but a regime in which Palestinian testimony becomes intolerable the moment it appears without authorization. The problem was never confined to content. It lay in the conditions of appearance themselves. Palestinian speech, once unmediated by institutional permission, is rendered suspect, excessive, or injurious by default.

This logic does not stop at the threshold of contemporary cinema. It extends backward into the archive, shaping in advance what survives, what circulates, and what remains buried. In this sense, Bakri’s struggle belongs to a longer history in which Palestinian images are not merely contested after the fact, but are preemptively rendered legally, institutionally, and epistemically inadmissible.

Any serious account of Palestinian cinema must confront the archive as a contested site of power rather than a neutral repository.

It is precisely this deeper infrastructure that Looted and Hidden – Palestinian Archives in Israel by Rona Sela brings into view. Where Jenin, Jenin exposes the contemporary disciplining of testimony, Sela’s film excavates the prior condition that makes such disciplining possible. Across the twentieth century, Palestinian film reels, photographs, and documents produced by cultural organizations and filmmakers were systematically seized by Israeli military and state institutions. These materials, many of them recording everyday life, resistance, and collective self-articulation, were not lost through neglect or accident. They were actively taken, classified, and rendered inaccessible, sealed within military vaults and governed by restrictive regimes of permission.

What Looted and Hidden ultimately reveals is that the archive itself functions as a site of sovereignty. As Ariella Azoulay has argued, imperial violence does not end with dispossession but continues through the ongoing governance of images and archives, making the struggle over Palestinian cinema not only a battle over representation, but over the right to historical presence itself.Control over images becomes control over historical intelligibility. Palestinian cinema is therefore confronted not only with censorship after it speaks, but with a prior dispossession that determines in advance which images may enter public memory at all. Read together, Bakri’s ordeal and Sela’s excavation clarify a single structure at work: testimony is punished in the present because the archive has already been captured in the past. The struggle over Palestinian cinema, then, is not only about representation, but about who holds custody over history itself.

This is not an accidental loss. It is custodianship without consent. The archive becomes an extension of sovereignty. To speak of gaps in Palestinian film history without naming this structure is to aestheticize dispossession.

Jenin, Jenin belongs to this contested archival terrain. Its vulnerability is not exceptional. It is paradigmatic.

Delay, Memory, and the Limits of the Field

What increasingly distinguishes Palestinian cinema in its contemporary phase is not a turn toward memory as recovery, but an insistence on delay as a historical condition. This is not delay as mere postponement, nor as melancholic waiting, but delay as structure: the enforced suspension of political time, archival continuity, and historical arrival. Palestinian cinema does not simply inherit a broken past. It works within a temporality that has been systematically rerouted, where images are produced for futures that are then foreclosed, deferred, or rendered unreachable.

This condition is rigorously staged in Off Frame (Revolution Until Victory), 2016, by Mohanad Yaqubi, a film that refuses both nostalgia for revolutionary cinema and cynicism toward its failure. Yaqubi does not treat militant images as relics awaiting rehabilitation into a usable past. He treats them as gestures suspended midair, images whose political horizon collapsed before they could settle into history. The film’s central question is not why the revolution failed, but what becomes of images when history itself is forcibly interrupted. Revolutionary cinema appears here not as a completed chapter, but as an unresolved proposition that continues to exert pressure without resolution.

A related but distinct sensibility animates Emwas: Restoring Memories by Dima Abu Ghoush. The film reconstructs the destroyed village of Imwas through testimony, landscape, and absence, yet it pointedly refuses the promise of restoration. Memory does not culminate in recovery. It resists closure. What is restored is not the village itself, but the right to remember without illusion. The film operates in a register where return is no longer imaginable as restitution, but neither is forgetting acceptable. Memory is thus held in tension, neither redeemed nor relinquished.

Taken together, these works from 2016 signal a decisive shift in Palestinian cinema’s relation to its own archive. The archive is no longer approached as a repository that might one day be completed, nor as a source of authenticity to be reclaimed. It is approached as a delayed and contested structure whose incompleteness must be acknowledged as constitutive rather than accidental. The task is not to repair the archive, but to work ethically within its fractures.

It is at this point that the limits of the existing critical field become visible. The scholarship on Palestinian cinema has been indispensable in securing its intellectual legitimacy and historical visibility. Foundational works by Nadia Yaqub, Anandi Ramamurthy, Paul Kelemen, Hamid Dabashi, Nurith Gertz, and George Khleifi have mapped the field with rigor and care. Yet this very act of mapping has sometimes come at the cost of premature coherence. Visibility is too easily mistaken for resolution. Trauma risks becoming a stable analytic category rather than a continually renewed condition produced by ongoing dispossession. Nationhood appears as a horizon of aspiration even when its deferral is the very structure shaping cinematic form.

What these frameworks struggle to fully accommodate is a cinema that does not move toward synthesis. A cinema that does not promise reconciliation between revolutionary inheritance and post-revolutionary aftermath. A cinema that accepts delay not as a deficit to be overcome, but as the terrain on which it must operate.

It is here that Bakri’s work assumes its critical significance. Bakri neither resolves the militant legacy nor submits to trauma as destiny. His performances and films do not offer narrative consolation, nor do they stabilize suffering into identity. They practice endurance without redemption. His restraint, his refusal of spectacle, and his insistence on testimony without authorization place him at a difficult juncture between revolutionary aspiration and archival foreclosure.

Bakri’s cinema does not ask what comes after delay. It stays with it. In doing so, it exposes the limits of a field that is too eager to narrate Palestinian cinema as an emergence, arrival, or consolidation. What persists instead is a practice of remaining with interruption, of working without guarantees, and of sustaining presence in the absence of historical closure.

This is not a failure of Palestinian cinema. It is its most exact diagnosis.

After Bakri

Bakri’s passing leaves not a monument but a method. He modeled how to work under conditions that deny guarantees. He understood that Palestinian cinema persists not by accumulating into a stable canon, but by remaining available to retrieval, repetition, and reactivation under threat.

There was humanity in this practice. Those who knew him speak of warmth, generosity, and an absence of bitterness despite the costs he bore. His politics were never ornate. When he withdrew from an international festival in protest, his explanation was almost austere: “It is high time that Palestinians are granted full rights, like the rest of the world.

No metaphor. No performance. Only a demand so basic that its continued denial exposes the violence of the world that withholds it.

Palestinian cinema remains unfinished because its historical conditions remain unresolved. Bakri did not resolve them. He stayed with them.

In doing so, he offered something rarer than representation. He offered witness as practice, and presence as refusal.

Rest in peace.