PART TWO

In this intimate conversation, Sultan Somjee traces a quiet revolution in how peace is understood and practised, drawing on the philosophy of Utu to challenge bureaucratised reconciliation and recover peace as a relational, embodied act grounded in memory, land, and communal life.

The Path of Peace

I asked him, “What is peace in the vocabulary of Utu?”

With his tone almost reverent, “Peace,” he said, “is bodily sensed as Utu in oneself. That is the vocabulary of Utu — it lives in feelings. You sense it in another person, too. You know the saying, ‘I am because you are’? That is not philosophy, it is sensation. Utu is how one body feels the truth of another.”

He spoke of it as both intimate and expansive. “The sensing can belong to an individual or to a collective. Utu is felt as beauty, the kind you see in a sunrise or in the breath of the Supreme Being. It is sensed in others, the way Alama senses peace in Ua. It is also sensed in beings — there are peace animals like the tortoise — and in nature itself, in trees, in grasses, in the land.”

“The vocabulary of Utu is felt by sensing and expressed through the body — in the arts, in dance, in the telling of stories.”

I asked him whether peace could ever be built without reconciliation with the land itself.

“It is not so much reconciliation with land,” he said after a pause, “as appeasing it after violence or calamity, like a disease outbreak. When blood is spilled, the land becomes hot and angry.”

“We call the reconciliation ceremony Cooling the Land. It is necessary after bloodshed. Blood is heat; violence is heat. The land must be cooled for peace to return.”

“You cannot offer reconciliation when you have offended. You can only say, ‘Sorry.’ That is the thinking.”

Then, more quietly: “Healing the land is also part of it. The earth remembers what has been done to it. To cool it is to restore its memory to calm.”

Letting the silence hold the idea, he paused and said: “When the land breathes again, so do we.”

Cooling the Land

Among the rituals that moved him most deeply were those that treated the earth itself as the injured party. “I have followed what I call Cooling the Earth rituals in different cultural communities,” he said. “They are profound in the care and love they show to the land. They offer care without spectacle.”

Material culture, here, is not ornament but instrument. “Peace staffs carved from sacred hardwoods gain their power only after ritual consecration,” he explained. “They can halt a conflict when held aloft by an elder.” Women’s waist belts, worn just beneath the womb, protect life as women labour across harsh terrain, carrying firewood and water, pulling animals, walking long distances. “I have seen the losses they prevent,” he said. “The belt saves life. It becomes sacred. A symbol of restraint and of the life the community must safeguard.” In Turkana regions, the echicholong, the headrest or stool, is sometimes exchanged at reconciliation sites and so becomes a peace object as well. “Each item carries its own history, its own gesture of repair.”

He recalled an incident that reached him only as narration from one of his assistants in the semi desert north. A Western film crew had staged a violent scene in a village. When they left, the elders gathered quietly and performed a ritual to cool the land. “Violence enacted, even as performance, still unsettles the soil,” he said. “Communities know this intuitively. They repair what outsiders do not see.”

These, too, are forms of walking: movements of bodies, objects, and intentions across a wounded ground, asking it to breathe again.

The Path of Reconciliation

I asked him about the peace projects that fill government reports and NGO brochures, those fragile ceremonies of diplomacy performed beneath air-conditioning vents. “You’ve witnessed the limits of Western ‘Liberal Peace’ projects,” I said. “What is missing when peace is bureaucratized?”

His answer came slowly, as if to strip the question of its jargon before responding.

“Bureaucratized peace,” he said, “is an agreement signed on paper — a deal made, a handshake exchanged. It is not an embodied peace, not the peace as understood by communities who have lived through conflict.”

He looked almost weary as he spoke. “We have seen decades of such meetings in South Sudan, in the Congo. The same theatre repeats itself. Elite politicians and corrupt bureaucrats arrive dressed like European gentlemen, in suits, polished shoes. They meet in five-star hotels and luxury lodges. Nature is absent.”

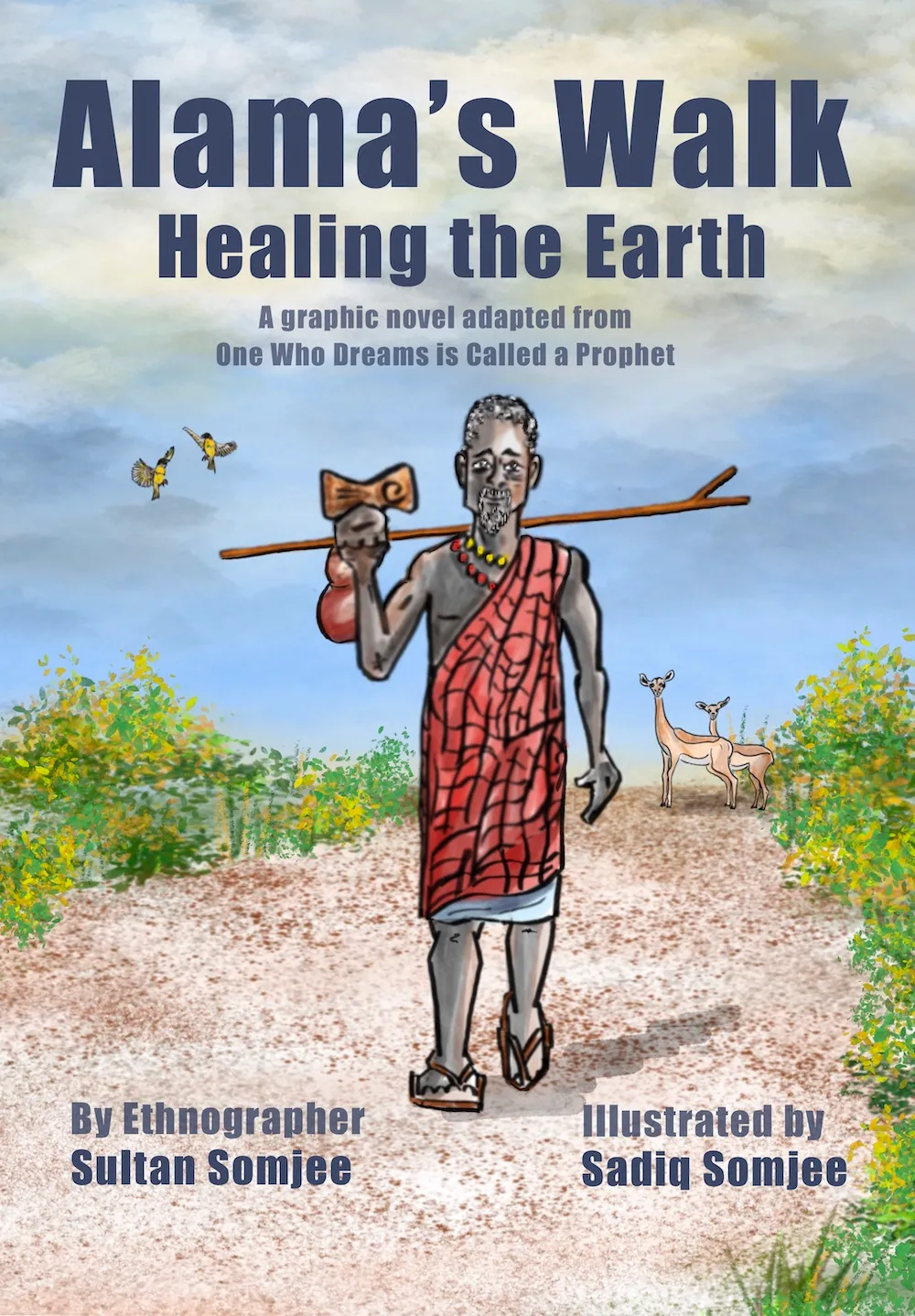

“I describe this from an Indigenous lens,” he continued. “In One Who Dreams Is Called a Prophet, I wrote a chapter on reconciliation as seen through Alama’s eyes. Some communities hold their reconciliation rituals at sunrise or sunset, when the land itself is calm — when the Supreme Being is listening. The setting, the hour, the ground, they are all part of the ceremony. Peace happens only when the world participates.”

He looked back at me. “When peace is not embodied, it is not peace. It becomes theatre.”

There was a precision in his phrasing that made the sentence feel carved, not spoken. “Peace,” he said, “is Utu, and Utu comes from mtu — human. Peace must be made by watu, by people. Mtu kwa mtu — person to person. That is what sustains a community. Peace cannot be made on paper. It must be felt by the community, it is communal.”

The phrase mtu kwa mtu lingered in the air, its cadence carrying more weight than any policy could hold.

I asked then, “Does peace, in your experience, begin as a social act or as an inner state?”

His response was immediate, almost tender. “Utu is social, and it is embodied, which makes it also an inner state. The philosophy of Utu acts on the individual through society, traditions, and beliefs. It is social because it is shared, but it lives inside the body. You feel peace in yourself as you feel it in another. That is the beginning.”

He looked at his hands again — the same hands that had held objects in countless rituals, the same hands that had touched soil in reconciliation ceremonies. “Peace is not taught,” he said quietly. “It is sensed.”

The silence between us was no longer absence. It was the form that understanding takes when words have done their work.

Rwanda and After

I asked how those years — the years of atrocity, of watching the unthinkable — had shaped him.

He did not answer at once. “I was stunned,” he said finally. “As Head of Ethnography at the National Museums of Kenya, I realised that we could do nothing. Conflicts and killings were happening all around us, in the Horn of Africa and within Kenya itself. The museum stood silent.”

He spoke the next words softly, almost ashamed. “I felt useless.”

Then his tone shifted from pain to quiet indignation. “But I was also humiliated. Soon after the Rwandan genocide, white reconciliation experts stormed into Kenya. They began setting up workshops on ‘Peace and Reconciliation’, teaching Africans how to make peace.” He let the irony sink in. “They came with their Euro-American agendas, replacing what already existed — the peace traditions of our communities. It was a spectacle.”

The pattern was painfully familiar. “In research it had been the same,” he said. “White researchers used their colour and money. People tolerated them with a residue of colonial awe. A researcher becomes an intruder when he does not know how to enter.” His response, over time, was to step aside from that posture. “I ask my students to be guests,” he said, “to write their ethics with the community, to know that they walk on someone else’s land.”

“It was painfully ironic that Americans came to teach Africans Truth, Peace, and Reconciliation — a philosophy that was already African, embedded in Utu.”

“Nelson Mandela and Bishop Tutu used it in South Africa as Ubuntu. Europeans later turned it into an academic discipline, packaged and sold it back to us as aid. Northern universities profited from it, using our traditions as their creation.”

He sighed, and then smiled, the kind of smile that comes from long endurance. “So I turned downward, to the grassroots. If the national museum could not act, the people could. I began to look for ways to bring peace traditions back to life.”

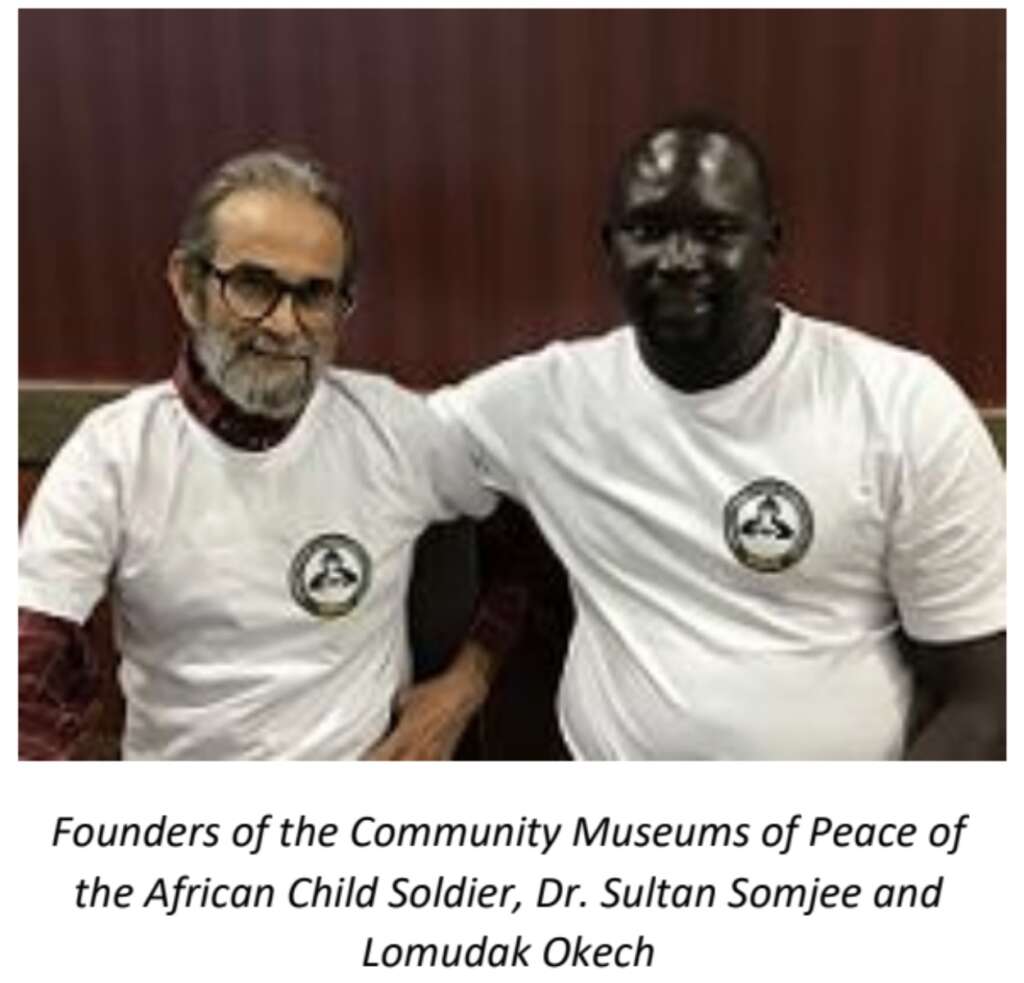

He spoke of the moment the idea took root: “I decided to create small museums — not to collect artefacts, but to hold conversations. We called them Community Peace Museums.”

At first, he had no funds. Then a small Christian NGO called the Mennonite Central Committee offered seed money. “We trained twenty-three young people to be curators,” he said. “Sixteen museums took shape. Each one different, each rooted in its own community, each carrying a local memory of reconciliation.”

He described them not as institutions but as gatherings. “They are not about display,” he said. “They are about living the heritage — the embodied arts, the languages, the objects used for peace-making, for social cohesion. That is where the philosophy of Utu still breathes.”

He paused, looking at one of the carved staffs on the shelf. “When atrocity enters the museum,” he said, “you must change what a museum is.”

There was silence again, and in it, a certain reverence.

He continued. “When peace rituals are performed, they happen in the open air, under trees, in the presence of the land. When I began to imagine these community museums, I wanted that same feeling — a space that listens, that breathes.”

“In those spaces, reconciliation is enacted, not exhibited.”

“That is how I learned what it means to be a witness,” he said. “Not to watch suffering from afar, but to keep walking toward it until it begins to speak.”

“These are not objects,” he said quietly. “They are beings that once spoke.”

He lifted a slender staff, its surface darkened by touch and time. “This was held during reconciliations between rival groups,” he said. “When one elder passed it to another, peace travelled through their hands. The object carried their intention.”

“In Utu, an artefact is not symbolic. It is relational. It lives between people. When you touch it, you enter a conversation that began generations ago.”

“This stool once held an elder who mediated conflict. The wood still carries that memory. To clean it with oil is to remember the sitting, to make peace again.”

What struck me most was how he never spoke of ownership. He never said “my collection” or “my artefacts.” Instead, he called them by their functions, as if naming kin. “I am only a custodian,” he said. “The objects know who they are. My duty is to keep their spirit visible.”

He looked around the room, then back at me. “Western museums preserve the form,” he said, “but not the soul. They protect the body of an object while killing its voice. The moment you take it from its people, you silence its tongue.”

In the Community Peace Museums, he had tried to return that voice. “We do not display peace; we enact the intention of making peace from living rituals,” he said. “Each artefact participates in that remembering.”

“This was used in blessing ceremonies. Milk was poured from it to reconcile enemies. Milk cools the land. Even the milk knows.”

“Some artefacts heal,” he said. “Not because they are magical, but because they restore continuity between memory and body. They calm the heart. They remind us we are still human.”

His words carried the slow rhythm of prayer. “As ethnographers, we must learn to listen to things,” he continued. “Not just their form, but their tone. Every object has an intoned quality — a vibration, a relationship. Our task is to make that vibration heard.”

He gestured toward a stool in the corner. “That mat is where elders sit to make peace. When people sit on it, their voices change. Their bodies soften. The stool teaches them how to speak.”

I realised then what he meant by a living institution. The Community Peace Museums were not about preservation but transmission. They existed so that memory could continue to act, to reconcile, to breathe.

Outside, the evening had turned to gold. The air was full of the slow murmur of night. Somjee stood by the doorway, still holding the staff. “These artefacts,” he said, “are like footsteps. Each one leaves a mark of peace on the land and touch of peace on the hand.”

“To walk, to hold, to remember,” he said, “they are the same act.”

The conversation turned to the idea that has guided Somjee for three decades: the museum as a living being. Not an institution, but an organism of memory.

“Community Peace Museums,” he began, “are not meant to display reconciliation. They are meant to enact it.”

He described how, in the early years, we had gatherings of peace museums, each museum became a meeting ground. “We would gather beneath trees, or in small halls, surrounded by the objects of daily life — stools, gourds, staffs and seedlings or branches of peace trees. Elders, women and youth came together. The rituals of peace were performed, not for show, but for transmission. What happened there was participatory. People danced, sang, told stories, cooked together. The body remembered.”

He paused and looked away, as if seeing those gatherings again — the shimmer of afternoon heat on red earth, the smell of woodsmoke and ochre bodies. “We did not curate exhibitions,” he said. “We curated conversations. We curated songs and dances, stories and material culture to bring forth conversations from them. We enacted memories. The feeling moved from one person’s body into another’s: I am because you are. Reconciliation is not a noun. It is a verb.”

When I asked whether he imagined these museums as sanctuaries, spaces where the moral imagination might be restored, he nodded. “Yes. That was always the dream,” he said. “They are civic sanctuaries and sanctuaries of civil societies claiming Utu from the government for dignity. Not because they are sacred in the religious sense, but because they return the sense of dignity to ordinary people. They remind communities that peace is within their reach, within their culture, within their bodies, embedded in their heritage.”

He spoke then of a larger vision — a museum of the future in Africa, born not from colonial taxonomy but from Utu. His eyes brightened as he described it.

“I imagine a place,” he said, “where Pan-African arts perform histories and Utu in its many forms. There will be no barriers between performer and audience, no separation between display and life. The museum will be a living sensorium — of dance, song, storytelling, touch, listening, and feasting. People will come not to look, but to feel. They will sense Utu through the seven senses.”

He leaned forward. “It will be a place of dialogue, where people gather to recover from colonialism and from what I call the neo-colonialism of forgetting and the ruling class’s obsession with coloniality. It will not collect the past; it will restore the present. The museum will be the heartbeat of community life again.”

For a moment, the air between us seemed charged with that dream — part vision, part invocation.

“I wrote a statement for it,” he said. “A vision of the Pan-African Museum of Utu. I have spoken about it at the Tangaza University in Nairobi, where my book is studied and where I supervise doctoral students. We have had meetings, online and in person and documents exchanged. But progress is slow. There is little enthusiasm, and no funding yet.”

He smiled, a gentle smile that carried neither resignation nor despair. “But my dream is strong,” he said, echoing the title of his book. “One who dreams is called a prophet.”

“Remember,” he said, “peace is not a theory. It is an act. The land remembers who walks on it.”

His words stayed with me long after I left, this idea that to walk is to witness, to reconcile, to dream. That the museum of the future may not stand behind glass at all, but beneath the open sky, where memory and wind speak the same language.

And somewhere, in that vast silence between steps, the walker becomes the museum: keeper of stories, bearer of peace, and pilgrim of Utu.

The step is where the soul of Utu begins.