“Monsters exist, but they are too few in number to be truly dangerous. More dangerous are the common men.” — Primo Levi, If This Is a Man (1947)

Marcel Ophuls died on May 24, 2025, at the age of 97. His death passed with quiet headlines, but the silence belies the magnitude of his legacy.

He had no patience for heroic narratives. He dealt in what history most fears: memory, not as tribute, but as trial. Moreover, in the days of a live-streamed genocide in Gaza, with Western democracies polishing their mirrors while smoke rises behind them, his absence feels like a warning unheeded. The architecture of memory has begun to rot. Amnesia has been institutionalised. Complicity is camouflaged as pragmatism. Language itself has frayed—no single word quite holds: genocide, occupation, resistance, deterrence. Everything spills. Nothing sticks. Nothing contains.

Ophuls’s death, then, is not just an end. It is a prod. A flicker against the great amnesiac beast that rolls forward, swallowing atrocity in real time, buffering tragedy into abstraction. His films were never meant to console those who turned away from him. They were crafted for the moment when turning away becomes impossible. What he sought was responsibility. What he demanded was moral clarity. With his death, the burden of that demand passes to us.

His passing elicited muted headlines. However, the quiet of that moment belied the noise he stirred over a lifetime. Ophuls was not merely a filmmaker. He was a forensic historian, a memory provocateur, and a moral provocateur. He refused the easy closure of national myths. He declined the cinematic grammar of uplift. What he offered instead was a method: irony as a scalpel, testimony as trial, duration as resistance.

Moreover, what remains is not just a legacy of films but an ethical imperative. In a time of rising nationalism, curated histories, and algorithmic amnesia, Ophuls’s work calls us to vigilance. His films are not messages in bottles; they are sirens.

Breaking the Silence: France, Myth, and the Anatomy of Complicity

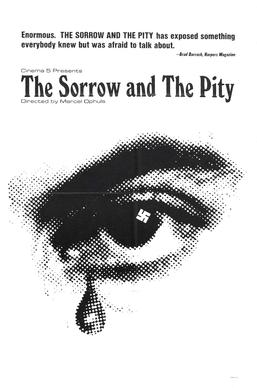

His breakthrough film, Le Chagrin et la Pitié (The Sorrow and the Pity, 1969), a 251-minute film, shattered the Gaullist myth of France as a nation of resisters. Subtitled “Chronicle of a French Town During the Occupation,” the film refuses the comfort of a singular national narrative. It presents a dense mosaic of testimony—interviews with collaborators, resisters, German officers, and ordinary citizens—arranged with forensic precision. Ophuls pioneered a form of documentary that allowed the subject to betray itself. By listening long enough, contradictions inevitably surfaced. By showing the banality of accommodation and the thin line between survival and betrayal, he built a narrative that was as morally disorienting as it was revealing.

As the film accumulates voices—some defensive, others oblivious, a few searingly honest—a composite image of wartime France takes shape, not as a nation of patriots but of negotiators, pragmatists, and opportunists. The effect was explosive. Banned from French television for more than a decade, the film circulated nonetheless, cutting into the national conscience like a surgical blade. Historian Henry Rousso argued that the film precipitated a shift from national myth to national memory, from glorification to reckoning (Rousso, 1991).

Ophuls’s strategy of allowing contradiction and ambiguity to accumulate recalls what Michael Renov described as the shift in documentary from exposition to expression, from the delivery of facts to the confrontation of subjectivity (Renov, 2004). Indeed, The Sorrow and the Pity can be seen as a visual embodiment of Hannah Arendt’s chilling insight into the ‘banality of evil’ (Arendt, 2006). The ordinary becomes the indictable; the casual conversation becomes a historical confession. This moral ambiguity challenges the audience, engaging them in a complex narrative.

One of the film’s most infamous interviews is with Christian de la Mazière, a former member of the Waffen-SS. He speaks not with remorse but with the polished detachment of a man curating his reputation. He does not seek forgiveness—he offers an explanation, rational, articulate, and chillingly unburdened. The power of this moment lies not in Ophuls’s judgment but in his restraint. The camera does not cut away. The audience is left alone with this unnerving composure. It is a cinematic masterclass in moral pressure—what Arendt identified as the bureaucrat’s calm and what Ophuls translates to film: evil made familiar, even reasonable.

The structure of The Sorrow and the Pity resists any narrative redemption. It is over four hours long and unfolds in two parts: one focusing on the city of Clermont-Ferrand, the other on a broader historical context. There are no heroes. Instead, we encounter layers of resignation, rationalisation, and selective memory. The film also embeds irony as a narrative tool. At one point, Ophuls cuts to a scene from Casablanca, with its stirring anthem of resistance. Juxtaposed with real-life recollections of collaboration and silence, the Hollywood fantasy becomes grotesque. Ophuls is not mocking the film—he is staging its dissonance. It is a cinematic tactic of deflation, showing us how myth can anaesthetise history.

The film is meticulous in its attention to the setting as well. Interviews are staged not against neutral backdrops but within homes, cafes, and streets—spaces where history unfolded in plain sight. The mundane becomes haunted. This insistence on lived geography grounds the testimony, connecting ideology to the landscape. We are reminded, again and again, that history happened not in abstraction but in ordinary spaces inhabited by ordinary people. This attention to detail immerses the audience in the narrative, fostering a sense of connection and engagement.

‘The Sorrow and the Pity’ was not only groundbreaking for what it revealed but also for how it altered French memory. As historian Rousso emphasised in The Vichy Syndrome, the film disrupted the national comfort zone. It opened the door to what he termed ‘the time of the historians’—a phase in which collective memory was no longer left to mythmakers but was rigorously contested, researched, and revised (Rousso, 1991). In this sense, Ophuls did not just make history visible—he altered its conditions of remembrance, enlightening and inspiring a new generation of filmmakers and historians.

Beyond Vichy: Ophuls and the Architecture of Moral Inquiry

After The Sorrow and the Pity, Ophuls pursued broader and deeper ethical inquiries. The Memory of Justice (1976) investigates the Nuremberg Trials while drawing comparisons to American and French actions in Vietnam and Algeria. Ophuls questioned whether those who judge war crimes might also be guilty of similar crimes. The film resists simplistic moral binaries, presenting justice not as a fixed truth but as a field of tension between legality, morality, and historical context.

Ophuls himself remarked on the formal and political complexity of the project: “I was asking to be indulged in my caprice of mixing and dubbing those 8½ minutes.” Critics, such as Vincent Canby of The New York Times, called it “a monumental achievement.” It remains one of the most intellectually ambitious documentaries ever made—a cinematic essay that challenges even the most engaged viewer to hold competing truths in mind.

Avishai Margalit’s conception of the “ethics of memory” is instructive here. For Margalit, memory is a moral act—not just a cognitive one (Margalit, 2002). Ophuls internalised this principle long before it was formalised. His films do not document events; they call viewers into an ongoing moral relationship with the past.

In Hotel Terminus: The Life and Times of Klaus Barbie (1988), Ophuls dissected the networks that allowed the Nazi war criminal to escape justice and live in Bolivia. More than a biographical investigation, the film becomes an autopsy of institutional forgetting. Ophuls noted, “Making this film was like an intense fight for the survival of memory itself.” Roger Ebert praised the film’s quiet moral ferocity: “Ophuls is a man with a highly developed sense of irony… he has often selected moments that are rich with self-contradiction.”

As Linda Williams argues in her essay “Mirrors Without Memories,” the strength of modern documentary lies in its ability to reflect the contradictions and elisions of public life (Williams, 1993). Hotel Terminus does just that. The viewer does not exit the film with a sense of clarity. Instead, one exits with a sharpened sense of discomfort—and a heightened demand for vigilance.

Pierre Nora observed that memory in modern societies has become a matter of “sites” rather than a living presence (Nora, 1996). Ophuls’s films push against this tendency. They insist that memory must remain active, volatile, and implicated. They are not monuments. They are alarms.

Ophuls’s influence radiates through a lineage of documentary filmmakers who share his commitment to moral inquiry and structural critique. British filmmaker Adam Curtis, in works such as The Century of the Self (2002) and HyperNormalisation (2016), constructs sweeping narratives that chart the interweaving of politics, psychology, and mass media. Like Ophuls, Curtis distrusts the coherence of official history. He collages archival footage, voiceover, and theory not to produce coherence but to expose it as artifice. If Ophuls is a cross-examiner, Curtis is a cartographer of illusion.

Belgian director Johan Grimonprez takes a more fragmented, postmodern approach, but his aims are not dissimilar. In Dial H-I-S-T-O-R-Y (1997), Grimonprez examines the media spectacle surrounding aeroplane hijackings, weaving together newsreels, fictional reenactments, and the writings of Don DeLillo. His later film Shadow World (2016), a damning exploration of the global arms trade, follows in Ophuls’s footsteps by focusing not just on events but on the rhetoric, silence, and institutional mechanisms that allow systemic violence to continue unchallenged.

Both filmmakers inherit Ophuls’s refusal of closure. They, too, understand as Pierre Nora reminds us, that memory is no longer something lived but something curated—and thus susceptible to manipulation. In this sense, Curtis and Grimonprez are the intellectual descendants of Ophuls. They expand his vision into the digital and post-9/11 age, but the ethical scaffolding remains the same.

What unites these filmmakers is not style but ethics. They do not seek to resolve history. They seek to implicate the viewer in it. In my review of Johan Grimonprez’s Soundtrack to a Coup d’État, I underscored how such films blend historical excavation with formal innovation to reveal the shadows beneath official narratives. Grimonprez does not merely challenge geopolitical amnesia—he scores it. That film, like Ophuls’s best work, functions as both exhumation and performance, drawing attention not just to what happened but to how memory is mediated and distorted. This aligns with Ophuls’s documentary ethos: not merely to expose the hidden but to interrogate the conditions of its concealment. In this, they all echo Ophuls’s guiding conviction: that to remember is not an act of nostalgia—it is an act of resistance.

Legacy, Lineage, and the Ethics of Watching

As Ophuls once told Frank Manchel in 1978, “My style is indirect. I work with irony with subtext. The point is not to lecture, but to let the subject condemn itself.” And they do. Time and again. That, too, is his genius: to speak through silence, to indict through framing, to trust the viewer to feel the tremor beneath the surface.

“You cannot fight lies with bombs,” he said in 2014. “You fight lies with history.”

In the age of complicity, this battle still lies before us. Ophuls is gone. However, the questions he forced us to ask are not. They endure, as do his films. As must our capacity to remember rightly, to witness fully, to refuse the comfort of forgetting.

The Memory of Justice is Ophuls’s most intellectually audacious project, not only for its subject matter but for its structural ambition. The film stretches across five hours, weaving between past and present, Europe and the U.S., legal scholars and soldiers, victims and policymakers. Its narrative elasticity resists moral convenience. It draws parallels not to accuse but to provoke unease. What connects Nuremberg to Vietnam is not equivalence but evasion—the language of necessity, of orders followed, of context too complex for judgment. Ophuls does not editorialise; he edits. He cuts between the courtroom gravitas of Telford Taylor and the bureaucratic indifference of modern military spokespeople, revealing an ethical grammar that transcends time.

Few filmmakers would dare hold a moral mirror to the liberal democracies that canonised the Nuremberg principles. In this sense, Ophuls was doing the work of a public philosopher. Like Arendt, he sought to understand how justice turns hollow. Like Margalit, he treated memory not as an archive but as an obligation.

The documentary’s ambition parallels that of Claude Lanzmann’s Shoah (1985), which also rejects conventional narration in favour of witness-driven testimony. However, where Lanzmann excludes archival footage to preserve the rawness of recollection, Ophuls weaves it in precisely to show how memory is manufactured—by the state, by the media, and by omission.

We must also consider Ophuls alongside Frederick Wiseman, whose observational mode contrasts sharply with Ophuls’s interrogative stance. Where Wiseman shows institutions in action, Ophuls shows the ideologies they cover. Where Wiseman is discreet, Ophuls is prosecutorial. The contrast is not aesthetic—it is ethical. For Ophuls, cinema is not only a record; it is an instrument of accountability.

This ethos remains evident today in the aesthetic of resistance found in activist documentaries, such as Laura Poitras’s All the Beauty and the Bloodshed (2022), which seamlessly blends personal narrative with systemic critique. Alternatively, in the algorithmic unease of Jonathan Perel’s Corporate Accountability (2020), which tracks the legacy of dictatorship in Argentine business archives. These filmmakers extend Ophuls’s central provocation: not simply what happened, but who benefits when forgetting becomes policy.

Thus, in an age of curated feeds and streaming forgetfulness, Ophuls’s method—long, complex, dissonant—remains vital. He reminds us that justice is slow, that memory is contested, and that silence is never neutral. This legacy bears global weight. In places where authoritarian revisionism is on the rise—from Brazil to India to Hungary—his work feels prophetic. His insistence on exposing contradiction over comfort and on refusing the analgesic of neat historical narratives has become an increasingly urgent stance.

We can imagine what Ophuls might have made of our present: of algorithmic propaganda, of live-streamed genocide and state violence, of a public attention span eroded by engineered distraction. He would have lingered. He would have listened. He would have insisted on the extended cut—the kind that does not let the viewer look away. In an era where media thrive on simplification, Ophuls’s enduring relevance lies in his refusal to make memory palatable. He filmed not for applause but for accountability. He trusted the viewer not with consumption but with confrontation.

Ophuls is gone. However, the questions he forced us to ask are not. They endure, as do his films. As must our capacity to remember rightly, to witness fully, to refuse the comfort of forgetting.—long, complex, dissonant—remains vital. He reminds us that justice is slow, that memory is contested, and that silence is never neutral. Ophuls is gone. However, the questions he forced us to ask are not. They endure, as do his films. As must our capacity to remember rightly, to witness fully, to refuse the comfort of forgetting.