Dear Dad: In Your Absence, Sorrow Lingers

My friend, I am jotting down these lines for you with the intention that I could write; you are unwritten, and with the hope that one day someone would write my story too.

Who is Allah Dad?

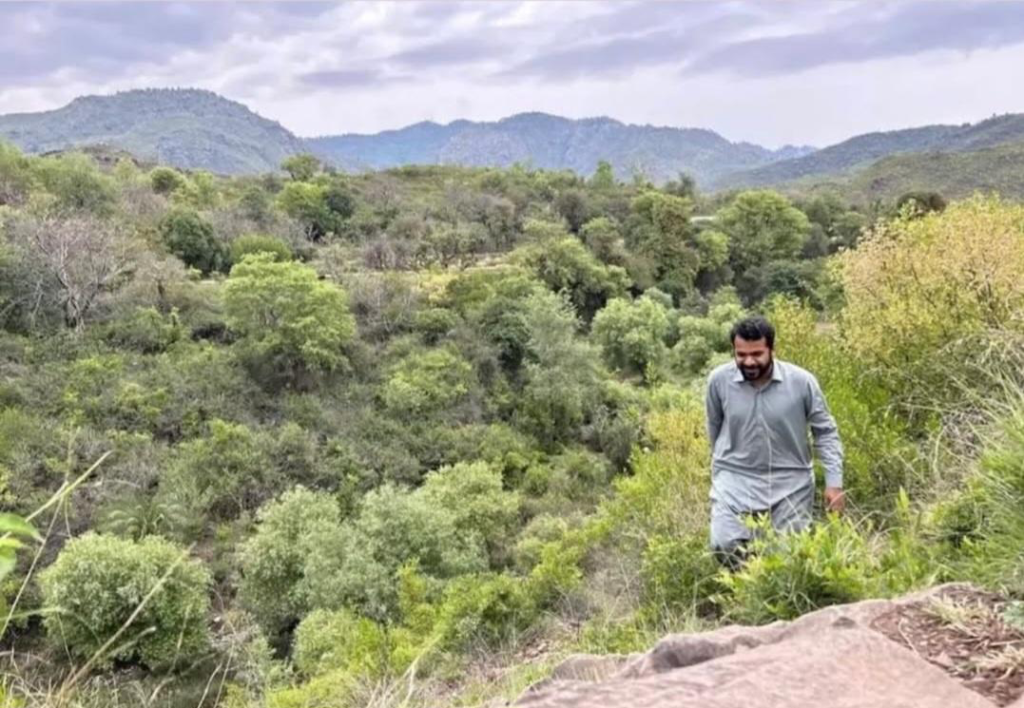

Allah Dad, son of Wahid, hailed from Turbat, Balochistan. He completed his secondary education at Atta Shad Degree College, Turbat, and later earned a diploma in Balochi. From 2016 to 2019, he studied general history at Karachi University, completing his BS before enrolling in an MPhil in History at Quaid-e-Azam University, Islamabad. Though he eventually left the program, he returned to his native city Turbat and founded Dodhmaan Publications, through which he published books and was working to expand it further in literary circles across Balochistan.

He was a scholar of history with a deep command of Baloch history, literature and cultural studies. He was working on multiple projects meant to enrich Balochi literature with a new vision, but before they could come to fruition, he was shot dead by state-sponsored death squads inside Ghamshad Hotel in Turbat. With his death, we lost not only a scholarly mind but also a man of rare intellect and integrity in the already endangered Baloch intellectual circle.

His target killing is not an unprecedented incident in Balochistan. Many Baloch intellectuals, writers, poets, and activists have long been targeted. Among them are renowned figures such as Saba Dashtiyari, Zahid Askani, Abdul Razaq, Sajid Hussain, Arif Barakzai, and many others—selectively silenced, erased, and destroyed by the systemic policies of the state. Their absence has left deep wounds in Baloch intellectual and political life. It is within this painful history that I remember you, my friend.

The First Encounter

It was a normal day—as normal as days can be in Balochistan. I was in a small room with three friends, laughing, teasing, and talking about everything from politics to literature. In times of war, we create small moments of laughter to forget, for a while, the unforgettable and the inflicted oppression that causes us trauma. Just a day earlier, I had been in a café with a friend, talking about those among us who seemed to be the right person in the right place. Our conversation turned to history, and your name came to our lips: Allah Dad. We did not know that while we spoke of you, you already stood at the edge of danger and were departing from us forever.

I remember the day we met. At Quaid-e-Azam University, in Majeed Huts, a friend introduced us to a brown-skinned man of medium height. Majeed Huts was a kind of lyceum at that time—a place for debates, discussions, and new friendships. Books were exchanged, and anyone could start a discussion while everyone shared their views. These remain only memories etched in our minds.

Then our friend asked, “Do you know him?” We shook our heads, indicating we did not. “He is Allah Dad, newly enrolled here—a writer, versatile and multi-skilled man, with a deep understanding of history, especially Baloch history and nationalism.” The friend added, “You just accompany him; he will do the rest himself.” And that’s how it happened—we were simply with you, and you did everything alone.

Later that evening, back in our room, you leaned against the wall and said, “These pseudo-writers are incompetent.” One of our writer friends bristled, but you clarified, “Yaar, I don’t mean you. I mean those who rely only on catharsis. Real craftsmanship demands responsibility.”

For you, writing and literature were sacred. It was not vanity, but conviction—a burden you carried until death. You despised imitation and warned that the essence of Balochi literature was being lost to those

who mimicked instead of creating something new.

A Friendship and a Mentor

From that moment, our friendship began. You were always questioning, debating, smiling, and teasing, but also pushing us to live with discipline and purpose. For us, writing was a pastime; for you, it was a responsibility—a rational labor.

Before you, words alone were mistaken for creativity among us. People who spoke endlessly were celebrated as if they were thinkers. But you showed us that even silence could be louder than noise—that creativity could be carried like a soldier carries a weapon, quietly, with conviction and purpose.

I still remember when I wrote my first draft for publication. You reminded me again and again: “Give a reference. Elaborate on your point. Don’t write empty sentences. Justify your claims with logic and evidence. Never fire into the air.” I remained lazy, insisting, “Yaar, I can’t do that much. This is enough.” But you made me see writing for what it truly is: a Herculean task, like turning ink into blood.

The Silence of Death and Enemies Within

But my dear friend, your death arrived in silence. In the noisy city of Turbat, inside Ghamshad’s dhaaba, your life—filled with dreams, ambitions, and a vision to reshape Baloch intellectual life and literature—was reduced to ashes. Everything ended with nothing. You were supposed to live, to make Balochi literature flourish, and to do many more things that were expected of you.

But the enemy knows whom to kill and whom to spare. They are clever, and we are naive. No one came to light candles at Fida Shaheed Chowk [1]. The so-called writers, poets, and human rights champions did not utter a word. You were buried in silence, like a seed—perhaps one day you will bloom again.

That night, when bullets pierced your body and you were no longer in this world, fear gripped us: it had been your turn, and now it could be ours as well. Indeed, we all live uncertain lives. And it is a fact that the greatest enemy is not only the one holding a gun. The most dangerous enemy is the one hidden among us, whispering to the oppressor, pointing at you: “In the noisy city of Turbat, there is a brown-skinned man carrying books, wandering from one bookshop to another.” That is how they found you.

A Nation of Individuals

The tragedy is not that we die—death comes to all. The tragedy is that in Balochistan, institutions are individuals. We think institutionally, we dream of academic discipline, but our institutions collapse when those individuals are taken. Their legacies fade, uncarried, uncontinued.

It happened with many others. It was not only your tragedy. The same happened to Shaheed Saba Dashtiyari [2]—no one carried forward his dream. The same with Sajid Hussain [3]—no one questions and critiques like him anymore. Again and again, the enemy is selective, and we are careless.

And Dad carried a rare gift (Dad also means gift): the ability to make others work. Even those with the slightest talent, you pushed into action. You roamed the Urdu Bazar in Karachi, searching for books and publishers, nurturing young voices. Only you had the courage for such work. You were a man of praxis indeed. You lived as a rational being, and I believe even in another life, you would remain one.

In Your Absence

We buried you in silence. But silence does not last forever. Like seeds, you may rise again—in us, in others, in words that refuse to die, and in a cause nourished by the blood of thousands. Yet, my dear friend, in your absence sorrow lingers, and your place remains vacant. I only hope your legacy will continue.

The inscription on the tombstone, written by him in Balochi, reads: “Leave me. My name is not important; what I desire is that good literature be translated into Balochi.”

Notes

1. Fida Shaheed Chowk—A central square in Turbat city named after Fida Ahmed, a Baloch leader who was killed, often used as a symbolic site of protest and remembrance.

2. Saba Dashtiyari (1953–2011)—A renowned Baloch scholar, poet, and professor of philosophy at the University of Balochistan, assassinated in Quetta.

3. Sajid Hussain (1981–2020)—A Baloch journalist and editor of Balochistan Times, who lived in exile in Sweden. He disappeared in March 2020 and was later found dead in Uppsala. His death raised international concerns about transnational repression of Baloch dissidents.My friend, I am jotting down these lines for you with the intention that I could write; you are unwritten, and with the hope that one day someone would write my story too.