“The occupied territories have the dubious distinction of having become a failed state before even becoming a state.” (International Crisis Group, 2007).

The international spotlight is back on Gaza. Israel’s 31st May attack on the six-ship flotilla carrying humanitarian aid to the Gaza Strip has dominated news headlines in the West and beyond; from Johannesburg to La Paz pundits, politicians and the public are asking, ‘How can we assist Gaza? How can we ensure a better humanitarianism?’ While Gaza, barely recovered from the Israeli onslaught of eighteen months ago due to the ongoing blockade, remains desperately in need of international assistance, there is another set of questions that we need to be also asking if we wish to see peace in the region: how did Gaza become a problem largely for the aid community? Where did the dream of a Palestinian state go? And, how has the international community been complicit in this reduction of Gaza in popular and policy-making circles as the paradigmatic humanitarian casualty? Since the ‘high point’ of the signing of the Oslo Accords in the mid-1990s, Palestinian prospects for statehood have rapidly diminished to the point where today Gaza has effectively been rendered little more than a humanitarian problem. There has been a steady erosion of discussion of Gaza in political terms except within the context of the politics of humanitarianism, particularly following Israel’s imposition of the blockade in June 2007.

The reasons for this shift pre-date the election of Hamas and its subsequent boycott. Palestinian statehood has been set back for a number of reasons, not least of all Israel’s role in continuing to establish ‘facts on the ground’ inimical to a two-state solution despite a rhetoric of peace and progress. International aid however, is at once both reflective of and has been implicated in this process of hastening the recasting Gaza as a focus for the outpouring of our sympathy, rather than an empowered political cause to which we lend our support. . Although aid to the Palestine has delivered some successes, during the official years of the peace process aid failed to deliver on its promise of supporting Palestinian statehood and in some senses even helped to fund its demise.

The Oslo years: ‘peace’ under occupation

Since the signing of the Oslo Accords foreign aid has played a major role in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, with both the Israeli and Palestinian administrations benefiting from Western (and in the Palestinian case, also Arab) largesse. The West Bank and Gaza Strip has been the recipient of one of the highest and longest sustained per capita aid disbursements in the world. The period following the signing of the Declaration of Principles had been one of high hopes and eager expectation as many in the region and in the international community believed that the Oslo Accords had ushered in a profoundly new era in Middle East relations. Donors met in Washington just two weeks after the historic handshake on the White House lawn to pledge an initial $2.4 billion in assistance to the Palestinians to prop up the agreements.

Notwithstanding sincere intentions, aid was however, deployed in support of a peace process that was fundamentally flawed from the outset. Despite being hailed as an historic achievement, as is now well-known, the Oslo Accords failed to address the final status issues of refugees, borders, settlements and Jerusalem crucial for the formation of any viable Palestinian state. The deepening economic and territorial undermining of the Palestinian state during the Oslo years was in large part attributable to the many inequities written into the text of the agreements themselves. Sidestepping much of the body of international law relevant to the conflict, Oslo favoured instead a formula of bilateral negotiations between two fundamentally unequal interlocutors.

By ignoring the political context of the continuing occupation that intensified under Oslo, aid’s effectiveness was limited from the start. While in many contexts donor support of peacebuilding has been a necessary condition of successful peace transitions, one of the biggest limitations of aid is the difficulty in bringing about peaceful outcomes should there be strong counter-veiling forces inimical to peace, such as the ongoing occupation by Israel. As Sara Roy has painstakingly demonstrated in a number of excellent works, Israel has long engaged in a deliberate policy of de-development of the Gaza Strip through which it has subordinated the Palestinian economy to its own, deliberately stripping it of its capacity for production in an attempt to undermine it entirely. This already precarious state of affairs was subsequently worsened by the system of closures that intensified during the years of the peace process. Justified under the by now all too familiar guise of protecting Israeli ‘security’, in 1993 Israel instituted the first hermetic closure of the Gaza Strip. This regime of closures impacted severely on the flow of labour and trade into Israel, which had been the lifeblood of the Gazan economy. Far from tackling this colonial relationship, the Oslo Accords effectively formalised the economic hierarchy that existed between Israel and Palestine continuing Israeli control over the factors of production in Gaza. The Paris Protocol moreover, formalised the de facto customs union that had existed between Israel and Palestine ensuring continued Palestinian dependence.

Aid without engagement

Yet, despite the fact that the feasibility on the ground of a Palestinian state diminished with each successive year, rhetorical support for it continued to increase over the course of the 1990s with positive assessments by major players such as the World Bank. This mismatch between rhetoric and reality was in part explained by the reluctance to upset Israel, which was driven by donor concerns not to ‘rock the boat’ for fear that this could derail a peace process in which the international community had invested heavily both diplomatically, and increasingly, also financially. The US in particular was keen not to antagonise Israel. As a result, there was an over-emphasis on ensuring Israel’s security needs (as determined by Israel itself) as a precondition for progress on other fronts, a pattern that has become well-entrenched in Israeli-Palestinian negotiations.

Aid has further hampered the Palestinian struggle for statehood by effectively subsidising the Israeli occupation of Palestine. In addition to the moral outrage that this breach of Israel’s international legal obligations invokes, by absolving Israel of its financial obligations towards the populations under its control, it has further served to hamper Palestinian prospects for statehood by reducing Israel’s incentives to seek a durable solution. While to hold aid responsible for the problems in the region is to misapportion blame, knowing that the donor community will eventually foot the bill with little more than tokenary criticism of Israeli actions allows Israel to periodically raze the physical bases of Palestinian statehood in various ostensibly security motivated incursions into Palestinian territory that destroy vital infrastructure and retard development.

Yet, instead of taking Israel to task, the international aid community has consistently refused to use international assistance (for example through donor conditionality) as a means to try and push Israel in a direction more amenable to Palestinian statehood. Donor unwillingness to challenge these impediments has meant that billions of dollars of aid money had failed to significantly improve life for the Palestinians and prepare the ground for peace within the context of a two-state solution. Instead, by ignoring Israeli policies inimical to Palestinian independence (both before and after the start of the Oslo process), aid is, as Larissa Fast has noted, at best just a “band aid” on an increasingly sore wound.

Burying Oslo: the shift to humanitarianism and basic survival

It is of little surprise then that despite the outpouring of assistance, the political and economic situation on the ground worsened towards the end of the 1990s. Burying the decade-long Oslo peace process, the outbreak of the Al Aqsa Intifada in 2000 significantly hastened the demise of a viable Palestinian state in Gaza. Coming on the heels of the failure of July’s Camp David summit, the Intifada was the spontaneous expression of Palestinian frustration over a peace process that had yielded neither economic, nor political improvements in the lives of most ordinary Palestinians. As a result of the violence the donor preference for aid without serious engagement continued and indeed intensified as primarily developmental forms of aid were replaced by humanitarian relief in an explicit shift from ‘state-building’ to bare survival. Instead of racketing up the pressure on Israel, the international community again used aid as a substitute for politics. Not withstanding that this transition in the form of aid was instituted to help the population cope on a day-to-day basis, it has had major significance in terms of state-building, particularly for the Gaza Strip as humanitarian aid by its nature tends to bypass governmental structures in its delivery. Although intended as a temporary realignment of priorities, the Intifada marked a decisive turning point in donor engagement with Gaza.

This emergency assistance was increasingly channelled through multilateral humanitarian programmes such as those of the UN. Between 2004 and 2007 the size of UN multilateral humanitarian programmes doubled so that by 2008, the size of the UN appeal for the occupied Palestinian territory was topped only by the appeals for Sudan and the Democratic Republic of Congo. The centrality of emergency assistance to the economy and the lack of monopoly control by the Palestinian Authority has contributed to a reduction in the effectiveness of the Palestinian Authority (PA) which, in the interests of building a state should always have been given a clear leading role. This sidestepping of the ruling authority began even before the rise of Hamas and partly helped to shape the desperate social and economic milieu in which Hamas gained a winning majority of seventy-six seats in the 2006 legislative elections.

In contrast to a rapidly faltering Fateh-led PA, tainted by its association with the failed Oslo peace process, Hamas’ prescience in rejecting the Oslo Accords eventually yielded great political dividends for the group. Hamas’ success can be attributed to the interaction of a number of factors, both domestic and international but the flaws in the aid effort must be included in this list. Given that the huge flows of aid destined to Palestine following the signing of the Oslo Accords were ultimately disbursed to win the support of ordinary Palestinians for the Western-sponsored peace led by Fateh, Fateh’s defeat at the polls at the hands of Oslo’s most prominent rejectionists is a damning indictment of failure and the lack of tangible economic and social improvement over the course of thirteen years of aid payments.

The donor response to Hamas’ victory has however, only served to further entrench this counter-productive situation. Following Hamas’ election, the donor community immediately suspended aid to the PA. The Middle East Quartet (i.e. the US, EU, Russia and the UN) insisted that political and financial cooperation with the PA was conditional on recognition of the three Quartet Principles to which Hamas does not subscribe. With the boycott of Hamas, the disconnection between aid and state-building has only become more apparent with the explicit bypassing of state structures in the delivery of aid. As a result, aid is no longer, if it ever was, effectively directed towards achieving a two state solution. The Temporary International Mechanism (and the later Mécanisme Palestino-Européen de Gestion de l’Aide Socio-Economique (PEGASE)) instituted by the European Union as a way of alleviating short-term suffering while circumventing Hamas, has only further driven away the prospect of statehood and has helped strengthen Hamas’ popularity as the ‘resistance’. The ‘West Bank first’ approach of the Quartet under which the international community and donors engage with Ramallah under a resumed rubric of state-building, has only further deterred Palestinian unity and further isolated Gaza as the crisis-stricken pariah.

Gaza needs more than just a ‘better humanitarianism’

Concomitant with and partly as a result of the aid community’s lack of engagement with the occupation since 1993, the status of Gaza has been reduced from a political to a merely humanitarian issue. The shift in aid that coincided with the outbreak of the Second Intifada has hastened the de-linking of aid and peacebuilding by focusing on short-term relief measures, which have helped to instil a permanent state of crisis in Gaza. The Israeli blockade of the Gaza Strip, which has been in force since June 2007 and Hamas’ seizure of control have served to entirely reframe the debate on Gaza. As Ilana Feldman has argued, most advocacy and political pressure concerned with Gaza has come to focus on a better, more comprehensive and more real humanitarianism. In discussions in international forums such as debates of the UN, the Gaza issue is framed in primarily humanitarian terms as references to ‘suffering’ and ‘victimhood’ monopolise discourse on the territory. Israel’s condition that only ‘humanitarian’ (i.e. non-‘political’) goods should be allowed into the Gaza Strip has largely been accepted at face value by the donor community, which has subsequently limited its own aspirations for the territory to better humanitarianism. Progress is now measured in terms of the length of the list of goods allowed into the Gaza Strip. The bigger question of viable statehood has all but been forgotten with the focus on overcoming these impediments to Gaza’s day-to-day survival. The question of small victories and humanitarian benchmarks is indicative of the insidious tendency in situations of protracted suffering to normalise high levels of violence and deprivation by the repeated invocation of the crisis.

Redefining Gazans as the beneficiaries of humanitarian assistance and objects of concern has gradually altered the way that Gaza and even Palestine as ‘cause’ is seen on the international stage, stripping Gazans of agency in the eyes of the international community. A sustained and high profile disbursement of humanitarian aid helps to recast the population of Gaza primarily as a collectivity of ‘victims’, rather than aspirants to independence or other similar notions that convey a sense of agency. This situation clearly benefits Israel, which wishes to diffuse Palestinian aspirations for statehood. Yet despite Israel’s deceptive agenda, Palestinian aspirations to statehood remain resolute.

The urgency of recognition

Currently the international community’s aid effort in Gaza has two major strands. Firstly, aid is delivered on the understanding that it plays a vital role in containing what could otherwise threaten to be what a number of leading NGOs have dubbed a ‘humanitarian implosion’. On the other hand however, aid policy is used by the major (particularly Western) donor governments and Israel as a tool to put pressure on the Hamas regime with the hope of causing its eventual downfall. However, it is a mistake to treat Hamas as a temporary phenomenon since as many close watchers of Gaza such as Sara Roy note, the group has deep-rooted support and has struck several popular chords. Moreover, Hamas has succeeded in transforming itself into a major, legitimate force in Palestinian politics. Not only did Hamas come to power in what has widely been regarded as free and fair elections, but the group has taken a series of steps to initiate peace with Israel, despite propaganda to the contrary, on several occasions offering a hudna (truce), which has been rejected out of hand by the Israeli government. Peace in the region will only come when Israel and its powerful Western allies accept that the Palestinians have spoken. Undermining their popularly elected leaders impedes Palestinian aspirations for statehood and is profoundly unjust.

References

-Fast, Larissa (2006). ‘Aid in a Pressure Cooker: Humanitarian Action in the Occupied Palestinian Territory’, Humanitarian Agenda 2015, Case Study no.7, Feinstein International Center.

-Feldman, Ilana (2009). ‘Gaza’s Humanitarianism Problem’, Journal of Palestine Studies 38:3, 22–37

March.

– International Crisis Group (2007). ‘After Mecca: Engaging Hamas’,Middle East Report, no. 62, Brussels, February.

-Le More, Anne (2005). ‘Killing with kindness: funding the demise of a Palestinian state’, International Affairs, 81: 5, 981-999.

———- (2006). ‘The Dilemma of Aid to the PA After the Victory of Hamas’, The International Spectator, February.

-Roy, Sara (1999). De-development Revisited: Palestinian Economy and Society Since Oslo, Journal of Palestine Studies, 28:3, 64-82

———- (1994). Separation or Integration: Closure and the Economic Future of the Gaza Strip, Middle East Journal, 48:1, 11-30.

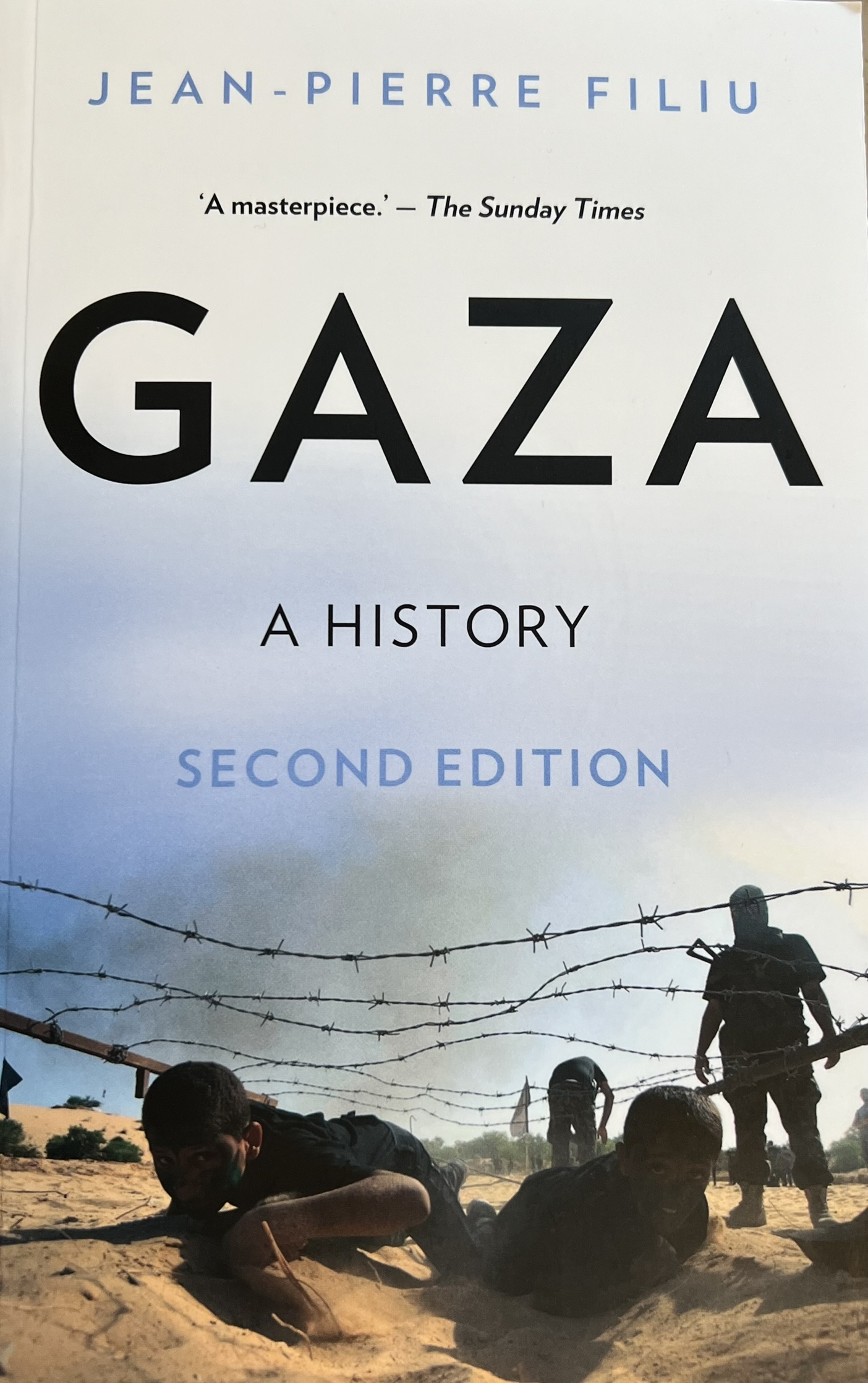

———(2007). Failing Peace Failing Peace: Gaza and the Palestinian-Israeli Conflict, Pluto Press.

-World Bank / Secretariat of the Ad Hoc Liaison Committee (1999). ‘Aid Effectiveness in the West Bank and Gaza’, Draft Report.

– (2008). ‘The Gaza Strip: A Humanitarian Implosion’, Joint agency report from Amnesty International UK, CARE International UK, Christian Aid, CAFOD, Medecins du Monde UK, Oxfam, Save the Children UK and Trocaire.