I had heard of “Nako” (Uncle) Mayar, who was looking for his missing son and to write his story I had to travel to the village Gilli in Tehsil Buleda. Buleda Tehsil is a peripheral region in an already peripheral province of Balochistan surrounded by mountains on all sides. It is located about 45 to 50 kilometers north of the capital city district, Kech, with a challenging, mountainous road .

A small village, Gilli, is one of the most underdeveloped areas in the region, lacking electricity, roads, and mobile network coverage. Educationally, it stands out as one of the least literate areas in Tehsil Buleda. Government schools are nearly non-functional, and private schools have been burned three times, further hampering educational development in the area. Economically, the area can be categorized into three main groups: a small number of labor migrants working in Gulf countries, limited agricultural activity, and the dominant reliance on border token systems for monthly income. Due to the lack of markets and reliable communication systems for agricultural goods, brokers or third parties manipulate prices, which discourages people from relying on agriculture. As a result, many have turned to temporary income from the border token system.

The journey from Turbat to Buleda, a route that should ideally take half an hour, stretches far longer due to the poor condition of the roads. These aren’t roads in the true sense—they are raw, rough, uneven tracks, where every bump tests your patience and endurance. In some places, signs of ongoing construction appear, but they offer little hope to the weary traveler.

As you drive, you notice more than 13 military checkpoints perched atop the surrounding mountains, their connecting roads branching off the main route. These checkpoints dominate the landscape. For first-time travelers, navigating this route is fraught with uncertainty. It’s easy to take a wrong turn towards one of these checkpoints, and in such a scenario, the consequences can be daunting. Without any mobile network coverage until you reach Soorap, travelers must rely on chance—waiting for another vehicle to pass by to confirm the correct path.

Midway through the journey, you come across a Zamyaad (vehicle) stranded near a mountain. Two women stand beside it, their faces marked with exhaustion. The vehicle has broken down, and with no phone network, the driver is left waiting for another traveler to offer help. It’s a scene that encapsulates the harsh realities of this region—an area where isolation and a lack of infrastructure turn minor inconveniences into significant crises.

When you finally reach Soorap, you get a brief glimmer of network, signaling your entry into the region of Buleda. However, the network fades away as you continue your journey forward. The road’s condition improves only slightly, and while the network returns briefly, there’s no internet, and it vanishes entirely once you move past Soorap. What should have been a simple 30-minute drive has now stretched to an hour and a half. The delay is not just frustrating but also indicative of how much the lack of basic infrastructure has held the region back.

For those traveling onward to the Gili area of Buleda or Menaz, the ordeal continues. The road—if it can even be called that—reverts to being a rough, shaky path. One glance at the terrain reveals another looming threat: the devastation caused by rainfall. The plains would flood entirely, making travel impossible and cutting off entire communities from the outside world.

To reach Gili, one must pass through several other areas. These areas too are shrouded in isolation, and as the sun sets, the entire region of Buleda becomes eerily calm. The bazaar shuts down, and residents retreat indoors unless an emergency forces them out.

The journey itself is arduous. Suffocating clouds of dust seep into the car, even with the windows tightly closed. Traveling at night presents a different kind of challenge. Dust kicked up by the vehicle hovers in front of the headlights, obscuring the view. In those moments, you can’t help but hold your breath, hoping no oncoming bike or car appears out of the haze.

Infrastructure is non-existent. There are no hospitals, no reliable roads. A local traveling with us summed up the plight of the region, saying, “They didn’t give us roads, but at least they could have built a hospital. On these shaky paths, if a pregnant woman needs help, it’s nearly impossible to take her to Turbat. Every bump becomes unbearable.”

Traveling from Soorap Buleda to Menaz, Alandoor, and finally Gili reveals a landscape of dust-covered homes, palm trees, “Drug-Free Buleda” chalkings fading on the walls, and military camps. The roads—or rather, the lack of them—are the greatest challenge. Without a local guide, losing your way is almost inevitable. Even at night, locals themselves often struggle to navigate the confusing routes, making the journey even longer compared to daytime.

As you pass through the villages, it becomes clear that the distance between areas isn’t the issue. A drive from one point to the next should take only 15 to 20 minutes. Yet, the absence of proper roads stretches this to over an hour. Adding to the difficulty is the lack of network coverage, which makes finding specific houses even more challenging.

Once you finally reach Gili, you stop at a small shop to ask for directions to an old man named “Nako” Mayar. The shopkeeper’s response is immediate: “The one whose son is missing?” You nod, and they point you toward his home.

Mayar’s residence is unmistakable—a single mud hut with a small kitchen beside, shaded by a solitary tree. As you approach, you step into the modest, dusty hut, where Mayar’s story quietly awaits.

Stepping into the hut, the first thing that catches your eye is a newly furnished motorcycle. On its back, a picture is displayed prominently—featuring Dr. Mahrang, and Sammi Deen. The cracked, muddy walls of the hut tell their own story, but your attention is drawn upward to a makeshift mud shelf. It holds a few glasses and plates, and nestled among them is a small framed photograph labeled Fateh Mayar. Surrounding the picture are five medal-like cups, their metallic gleam softened by dust.

Noticing your gaze, Nako Mayar smiles faintly and says, “There used to be more—over a dozen. But the rest were taken by the naughty children in the village.”

Nako Mayar is a 74-year-old shepherd who spent decades herding goats and sheep to support his wife, Paryatoon, and their five children. However, everything changed on June 14, 2023, and now his 14-year-old son, Shajan, has taken over the herd. Mayar abandoned his herd, and Shajan left his school, all for the same reason: Fateh.

Fateh, Mayar’s eldest son, completed his matriculation through private exams at Alandoor Government Primary School, which lacked proper schooling facilities. Earlier, he had studied up to class 5 at Saach School Gili Campus, a private school established by a local businessman in Buleda. The school offered free education to deserving and underprivileged students, and Fateh was one of them.

After school, Fateh would tutor junior students at the same school. He would return home around 2 o’clock, and after having lunch, he would teach other children at his house. The small amount of money he earned from teaching served as his pocket money.

In his native town, Fateh was known as a sensible, serious, and hardworking child. He often helped other children with their studies, earning their respect and admiration. Fateh made his pocket money by tutoring students, and even after school, he continued teaching children at home without charging them.

According to his mother, Fateh never stepped outside the house premises after sunset, nor did he ever indulge in fun or other activities. “I have always seen him immersed in his books,” she recalls.

One day, during a function at Saach School, Fateh delivered a speech on creating a drug-free Buleda. His words left a lasting impression, earning praise from both the school principal and the school’s owner.

A week after the program, the school announced that it would take 15 bright students on an all-Pakistan tour. Being one of the brightest students, Fateh was asked by the principal to nominate two friends to join him, and he gladly did so.

Excited about the trip, Fateh told his mother to pack his clothes. She gathered them and placed them in a shopper (plastic). Seeing this, Fateh hesitated and said, “I’m going to the city on an all-Pakistan tour. If my clothes are in a shopper, people will laugh at me.” He then urged his mother to borrow a bag from a neighbor. However, she replied softly, “I would be ashamed to ask the neighbors for a bag.”

Instead, she handed Fateh two thousand rupees from her own savings and suggested he use the money he had saved from teaching. Fateh had already saved two thousand rupees, which was just enough to buy a bag.

“I have enough money now! I’ll also buy a pair of sandals for father—Eid is near,” Fateh said eagerly.

Fateh, along with his two friends, Shay Mureed and Abdullah—whom he had nominated for the trip—headed to Turbat City for their shopping. They bought the necessary items for the tour, including a bag for Fateh. Afterward, they went to the house of one of their friend’s uncles to eat a meal. Once they had eaten, they prepared to return to Buleda.

As they got ready to leave, one friend started the bike, another opened the gate, and Fateh stood waiting outside. Suddenly, a white Toyota Corolla car arrived, and someone inside signaled for Fateh to come closer. Thinking they needed help, Fateh approached the car. Though at a short distance, three Frontier Corps vehicles were stationed. However, as the car window rolled down, Fateh sensed danger and turned to run back to his friends. Before he could get away, Frontier Corps personnel arrived and apprehended Fateh. His friends protested, asking why he was being abducted, but the Frontier Corps detained and enforcedly disappeared them as well.

After seven days, both Abdullah and Shay Mureed were released and returned to Buleda, but Fateh never came back.

Paryatoon, his mother, now weary and feeble, sits in her old, faded Balochi doch. The once-vivid embroidery has dulled, covered in dust. Haunted by regret, she murmurs, “I wish I had set my embarrassment aside and gone to ask for a bag. At least I wouldn’t have lost my son.” Tears well up in her eyes as her voice falters under the weight of her grief.

“I used to collect 10 rupees and sometimes even borrow, just to let Fateh get an education,” Nako Mayar expressed, with a loud cry shaking anyone’s conscience. “Curse upon me for allowing him to get an education… or else he would never have disappeared.” And God’s wrath upon those forces who took him away from me.”

His wife then tells him not to curse anyone. “My flesh and bones curse them,” he replies, his voice breaking with a loud burst of cry. Anyone sitting around him would feel the weight of guilt from hearing his cries, or they would be moved to tears themselves.

“May they rot the way they have rotted my old heart,” he says, his voice cracking with pain as he wipes his tears with his Balochi chador.

Nako Mayar says he doesn’t know whether his son is alive or dead. “It’s been 18 months, and no one has provided me with any information about him,” he says, his voice heavy with despair. “His two friends who were released told me nothing except that they were in separate cells but could hear each other’s voices in the dark.”

Fateh was just 16 years old when he was forcibly disappeared. He didn’t have a CNIC as he was under 18 and only had a B-form. “Though he grew a beard early and looked older than his age, he was still just a boy,” says Nako Mayar.

Soon after Fateh’s enforced disappearance, Nako Mayar went to Bit, Buleda’s police station, but his son’s disappearance case was not filed.

Whenever a person is released, whether in Turbat or Buleda, Nako Mayar visits them at any cost. Whether he can afford the travel or not, he somehow manages to go and ask about his son. “I ask them if they have seen him, and knowing it’s very dark there, I ask if they have at least heard his voice. They always say, ‘No.’”

When Balach Mola Baksh was killed in a fake encounter in 2023 by Counter Terrorism Department (CTD), the old man borrowed money from his neighbors and went to Turbat, fearing they might do the same to his son and joined Baloch Yakjehti Committee’s sit-in at Turbat.

“They were all saying that a long march would be carried out across Balochistan and then to Islamabad,” Nako Mayar recalls. “I told them, ‘I only have 2,000 rupees; how will I manage to march to Islamabad with you?’ They said, ‘Nako, you just come with us, don’t worry about travel expenses.’ So I went to Islamabad and returned with the same 2,000 rupees.”

As soon as the Baloch Yakjehti Committee’s march reached at Tool Plaza Islamabad, they were stopped by a heavy presence of Islamabad Police. The police didn’t allow them to proceed to the press club and started beating and arresting the marchers, including women, children, and men. Amidst the chaos, a student arrived with a taxi and took Nako Mayar to the Islamabad press club, where other families of missing persons were already protesting.

Then the police stormed the press club as well. “Above all, they scattered the tent and threw it upon us. We all fell on top of each other; we didn’t know who was falling on whom—men, women, and children were all trapped under the tent. We were helpless,” Nako Mayar remembers.

“According to our Baloch tradition, we men respect women and always try to protect them,” Nako Mayar says. “But here, we could do nothing. They fell upon us, and the women were dragged and arrested while we watched in shock, helpless.”

It was the first time Nako Mayar had stepped outside of Turbat, now finding himself in the capital of Pakistan for the safe release of his son. “I saw women being beaten, their chadors falling to the ground, and the police stepping on them. At that moment, I wished the Earth would open up and swallow me whole… My eyes couldn’t bear this humiliation.”

When the police used water tankers in the cold weather of Islamabad, showering the protesters, Nako Mayar still couldn’t believe his eyes. He remembered leaving his children and wife all alone, believing that in Islamabad, their loved ones would be released, and their voices would be heard. “We were so hopeful, and upon reaching, they dismissed all the hopes of us poor people who had never stepped outside of our homes before,” he says with a heavy heart.

He remembered that in the middle of facing the freezing cold water, he was shivering to the point of collapse. Most of the people were arrested, and more police vans were on their way to make further arrests. At that moment, a police officer noticed Nako Mayar and asked a nearby Baloch student who was helping him. Though Nako Mayar didn’t understand Urdu, the student later told him what had been said. The officer had asked why old people like him were there. The student replied, “Their loved ones are missing.”

Nako Mayar reflects, “They don’t even know that our people are disappeared, and that’s why we have come this far. Or else who would leave their homes behind, travel so far in this freezing winter, and endure such treatment?” As soon as the student relayed those words to Nako Mayar, he too was arrested.

“I was amazed at what was happening. I didn’t know what to do. I saw the police arresting women, students, and children, throwing them into the police buses.”

In the midst of the chaos, two Baloch students managed to take Nako Mayar to an apartment. Afterward, the Baloch Yakjehti Committee (BYC) set up its camp in front of the Islamabad Press Club. “The camp lasted for a long time; we sat through cold days and nights, but nothing happened.”

This was not the only protest he participated in. He has been part of various protest camps in front of the Turbat Deputy Commissioner’s office and Fida Chowk. The last time they set up a camp was in front of the Deputy Commissioner’s office in July 2024. On the 25th of July, an FC officer and Hothman, the district chairman of Kech, assured them that if they called off the sit-in, their sons would be released. “But I believe it was a deliberate attempt to stop us from joining the Baloch National Gathering,” he said.

During the July sit-in, the children, men, and women endured various skin diseases due to the scorching heat of Turbat. “We would faint, stay awake the whole night and day because of the heat waves, but nothing happened. May the torment of our hearts fall upon those who play with our pain,” he expressed.

“Fateh was a sensible child,” Paryatoon says, tears welling in her eyes. “He would never step outside the house after sunset, nor had he ever been out of the city. His only fault was that he wanted to help us by getting an education.” She pauses, her voice trembling. “One day, one of Fateh’s friends asked me what kind of magic I had done to him, that he never indulged in any bad habits or addiction. I just smiled and felt proud.”

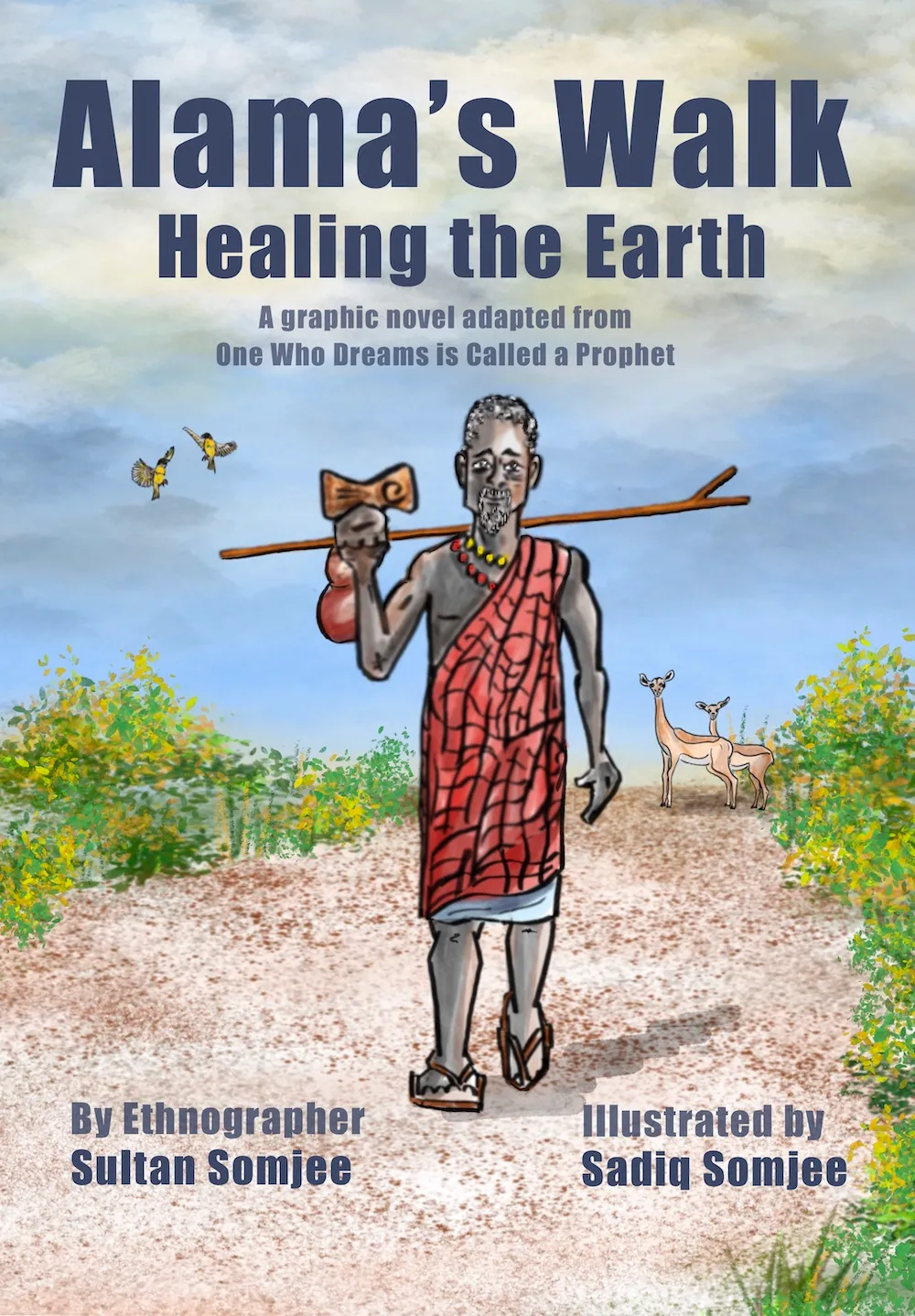

Now, Mayar carries the guilt of not taking Fateh to herd goats and instead encouraging his education. His mother, Paryatoon, regrets not asking the neighbors for a bag. His brother, Shahjan, blames himself for not stopping Fateh when he saw him delivering a speech against the drug mafias, fully aware of how powerful those people are. Together, they recall every little detail of Fateh’s life, clinging to their memory. In their small, humble hut, Fateh lives on through a framed photo surrounded by the small trophies he had proudly won in school competitions.